This article is written by Pooja Biswas, of 8th Semester of South Calcutta Law College, University of Calcutta pursuing BA LLB, during her internship at LeDroit India.

KEYWORD –

Auditor rotation, Companies Act 2013, Mandatory rotation, Audit independence, Auditor tenure, Cooling-off period, Statutory auditors, corporate governance, Section 139, Section 140, Auditor reappointment, Audit firm rotation

ABSTRACT –

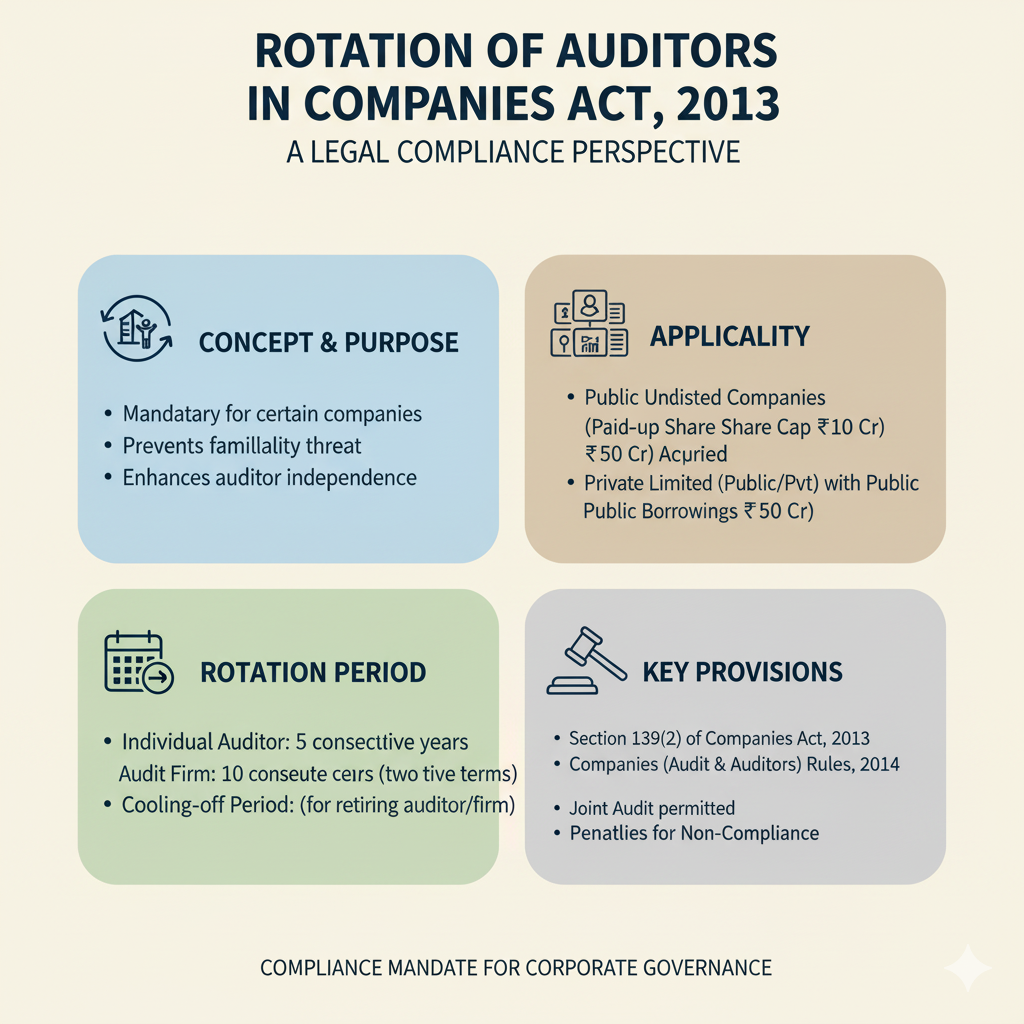

Mandatory rotation of auditors was introduced in the Companies Act 2013 to boost auditor independence and strengthen corporate governance. Section 139 requires rotation of auditors for specific companies after a predetermined period, in a bid to prevent long-standing associations that can threaten objectivity. This article looks at the specifics of rotation of auditors in the Act, its provisions, challenges of implementation, and impact on audit quality. By examining legendary judgments and recent case laws, we discuss the real-world implications of these regulations, unveiling the changing scenario of statutory audits in India.

INTRODUCTION –

Auditors play a pivotal role in ensuring the accuracy and reliability of financial statements, thereby upholding stakeholder trust in corporate entities. Recognizing the potential risks associated with extended auditor-client relationships, the Companies Act 2013 incorporated provisions for mandatory rotation of auditors. This measure seeks to bolster auditor independence and mitigate conflicts of interest. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of these provisions, their rationale, and their practical application within the Indian corporate framework.

LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK –

The Companies Act, 2013, in Section 139, lays down a formal framework for auditor appointment and rotation, ensuring independence and accountability of financial reporting. The legislation sets particular tenure limits to avoid overfamiliarity between auditors and the management. For individual auditors, the Act imposes a maximum term of one term of five consecutive years, and for audit firms, a limit of two consecutive terms of five years. To add further strength to auditor independence, a five-year cooling-off period is mandatory before the same auditor or audit firm can be reappointed by the same company. This is the provision that plays a very significant role in combating familiarity threats and bringing about a new vision in the auditing process. The use of auditor rotation can also be applied to firms where the effect of audit independence is most felt.

These provisions are compulsory for all listed companies, unlisted public companies having a paid-up share capital of ₹10 crore or more, and private companies having a paid-up share capital of ₹50 crore or more. Even those companies having public borrowings from banks, financial institutions, or public deposits to the tune of ₹50 crore or more also come under the rotation mandates. Such thresholds ensure that large bodies, which have a greater impact on the financial environment, follow more stringent regulatory standards, thus fostering transparency and improving company governance.

RATIONALE BEHIND MANDATORY ROTATION –

Enforcement of compulsory rotation of auditors fulfils various important goals with the aim of improving corporate governance and financial transparency. One of the main motivations for introducing this provision is to improve auditor independence. Periodic rotation prevents auditors from building long-term relationships with the company’s management, which may make them less objective and impartial. By restricting tenure, the legislation ensures a new and impartial eye in financial audits.

Another strong reason is the avoidance of familiarity threats. If auditors stay with a company for long periods, there are chances of complacency, and this may result in negligence in identifying financial anomalies. The insertion of fresh auditors from time to time creates a more sceptical and impartial audit process, avoiding such risks.

In addition, required rotation also supports transparency and accountability in company governing structures. An audit system rotating over a period of time injects increased stakeholder confidence because it showcases the fact that the financial statements come under review from different independent experts. It enhances investor confidence but also matches world best practice and ensures financial reports are credible and free of risk of possible conflicts of interest.

CHALLENGES –

Mandatory auditor rotation, as much as it is meant to be beneficial, has a number of challenges that can affect the effectiveness and efficiency of the auditing process. One of the major challenges is transition management. Constant changes in auditors can result in knowledge gaps, as new auditors might not be as familiar with the company’s financial past and internal procedures as their predecessors. This movement can also lead to added expenses, as organizations might need to put more funds into enabling the process of handing over. Another problem is the shortage of auditors, especially in niche sectors where there are few firms with the related expertise. Companies then find it difficult to obtain competent auditors to satisfy regulatory requirements while keeping audit quality high. This shortage may also concentrate audit work in the hands of a few firms, decreasing competition and having an impact on audit fees.

Also, new auditors need some time of initial familiarization to get to know the company’s operations, financial arrangements, and industry-specific details.

This learning curve could temporarily affect the quality and effectiveness of audits, as auditors could take some time to recognize risks and evaluate financial statements with the same level of depth as their predecessors. While rotation is intended to enhance audit independence, the challenges underscore the importance of achieving a balanced solution to avoid jeopardizing audit effectiveness during the transition.

SUGGESTIONS –

Companies will have to adopt strategic plans for ensuring efficient enforcement of auditor rotation under Section 139 of the Companies Act, 2013. A methodical process of transition would facilitate efficient transfer of knowledge among outgoing and new auditors so that any inconvenience is kept at a bare minimum. A greater available pool of eligible auditors, particularly in focused industry segments, would avoid their concentration in handfuls of companies. Regulatory bodies like NFRA and MCA must strengthen oversight and lay down strict rules for non-compliance so that there is equitable implementation of rotation policy. To overcome the early familiarization issues, business entities must extend new auditors access to historical audit reports and books of records, with digitalized financial reporting accelerating the process even further. A staged implementation process can be best suited for SMEs, offering more time for compliance. Consolidating India’s policies with the best worldwide practices adopted in the US and EU will result in more efficient regulation.

Finally, inducing voluntary rotation through incentives such as lesser compliance burdens can promote proactive corporate governance. Implementing these practices will enable India to have a balance between auditor independence and audit efficiency so that the policy enhances financial transparency without impairing business functions.

ILLUSTRATIONS –

- Pipara & Co. LLP v. Tourism Corporation of Gujarat Limited (2021) –

In this case, Pipara & Co. LLP was appointed as the statutory auditor for Tourism Corporation of Gujarat Limited (TCGL) for financial year 2020-21. Yet, TCGL then stopped directing work to the firm and terminated their appointment without notice.

The main issue that came before the Gujarat High Court was whether TCGL’s cancellation of Pipara & Co. LLP’s appointment without complying with the due procedure under Section 140 of the Companies Act, 2013, was justified.

The court held that the removal of an auditor prior to the lapse of their term must be in accordance with Section 140(1) of the Companies Act, 2013, which requires previous approval of the Central Government and affords the auditor a reasonable opportunity to be heard. The Gujarat High Court held that any default in these procedural steps makes the removal ineffective.

- Union of India v. Deloitte Haskins and Sells LLP & Another (2023) –

In this case, the Union of India had made an application under Section 140(5) of the Companies Act, 2013, for the removal of Deloitte Haskins and Sells LLP as auditors on the grounds of their involvement in fraudulent practices.

The issues that were paramount before the Supreme Court were:

- Whether the proceedings under Section 140(5) could proceed against auditors who had already resigned.

- The constitutional validity of Section 140(5) of the Companies Act, 2013.

The Supreme Court sustained the constitutional correctness of Section 140(5), highlighting that the provision allows the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) to discharge auditors who have committed fraud or abetted fraud. The Court went on to establish that the resignation of an auditor does not disqualify the NCLT from instituting or continuing proceedings under Section 140(5). Such proceedings can continue regardless of the auditor’s resignation.

- CDK Global India Private Limited, In Re (2017) –

CDK Global India Private Limited was incorporated in August 2014 but did not appoint its first auditor within the period of 30 days as required by Section 139 of the Companies Act, 2013. The appointment was finally made in August 2015, and hence there was a delay of more than one year. The central question before the Tribunal was whether delay in the appointment of the first auditor was an offense under Section 139 and if so, whether such an offense could be compounded.

The Tribunal declared that the offense under Section 139 is compoundable. Having regard to the bona fide reasons given by the company for the delay, the offense was compounded with a fine of ₹25,000 levied on the company and ₹1,000 on each defaulting officer.

- Graco India Private Limited, In Re (2017) –

Graco India Private Limited, incorporated in November 2015, delayed the appointment of its statutory auditors by six months, violating the timeline stipulated under Section 139 of the Companies Act, 2013.The key issue before the Tribunal was whether the six-month delay in appointing statutory auditors warranted compounding of the offense under Section 139.

The Tribunal observed that the company had proactively sought to compound the offense and had rectified the default by appointing auditors in August 2016. Given the company’s corrective actions, the offense was compounded with a penalty of ₹2.5 lakhs imposed on the company and ₹50,000 on each of the other petitioners.

- SPC & Associates v. DVAK & Co. and NISC Export Services Private Limited (2017)

SPC & Associates was chosen as the statutory auditor for NISC Export Services Private Limited for a period of five years. Nevertheless, there was a disagreement regarding audit fees, and thus, the company unilaterally hired DVAK & Co. as the new auditor without adhering to the statutory procedure under Section 140 of the Companies Act, 2013.

The main problem before the NCLT Hyderabad Bench was whether the de-enlistment of SPC & Associates and the appointment of DVAK & Co. without following the prescribed statutory procedure were valid.

The Tribunal held that the removal of SPC & Associates was not proper because it did not comply with Section 140, which requires prior sanction of the Central Government and a special resolution for the removal of auditors. Accordingly, the NCLT ordered the company to restore SPC & Associates as the statutory auditor until the next Annual General Meeting (AGM) and held the appointment of DVAK & Co. to be invalid.

CONCLUSION –

Compulsory rotation of auditors under Section 139 of the Companies Act, 2013 is an important provision to promote audit independence, prevent familiarity threats, and strengthen corporate governance. By putting a cap on the tenure of auditors and mandating a cooling-off period, the legislation helps ensure that the companies are put through periodic review by new auditors, keeping the risk of financial misstatement and conflict of interest at a minimum. Nonetheless, as useful as it is, issues like transition complications, shortages of auditors, and starting point familiarization challenges provide huge obstacles to its successful deployment. To achieve a delicate balance between audit independence and operating efficiency, businesses need to implement transition strategies, diversify the auditors’ talent pool, and harness digitalized financial reporting.

Regulators like NFRA and MCA will need to lead in enforcing conformity and solving problems in practice. Pioneering case judgments like Union of India v. Deloitte Haskins and Sells LLP and Pipara & Co. LLP v. Tourism Corporation of Gujarat Ltd. reflect the judiciary’s approach to imposing auditor rotation while maintaining procedural fairness. In the future, bringing India’s auditor rotation policies in line with best international practices and instituting incentive-based voluntary rotations can improve compliance and simplify the transition process. Through the implementation of strong oversight mechanisms and industry-specific solutions, India can successfully strengthen financial transparency, increase investor confidence, and maintain the integrity of corporate audits.

REFERENCES –

- Pipara & Co. LLP v. Tourism Corporation of Gujarat Limited – Special Civil Application No. 7342 of 2021, decided on June 17, 2021 (Gujarat High Court).

- Union of India v. Deloitte Haskins and Sells LLP & Another – Criminal Appeal Nos. 2305-2307 of 2022, decided on May 3, 2023 (Supreme Court of India).

- CDK Global India Private Limited, In Re – C.A. No. 19 of 2017, decided on March 17, 2017 (National Company Law Tribunal).

- Graco India Private Limited, In Re – CP No. 229.Chd/Hry/2017, decided on October 24, 2017 (National Company Law Tribunal).

- SPC & Associates v. DVAK & Co. and NISC Export Services Private Limited – CP No. 21/140/HDB/2016, decided on May 19, 2017 (NCLT Hyderabad Bench).

- Companies Act Integrated Ready Reckoner|Companies Act 2013|CAIRR. (2025). Section 139.Appointment of auditors | Companies Act Integrated Ready Reckoner|Companies Act 2013|CAIRR. [online] Available at: https://ca2013.com/appointment-of-auditors/ [Accessed 24 Mar. 2025].

- taxguru_in and Manish Dulani (2023). Rotation of Team of Auditor under Companies Act, 2013. [online] TaxGuru. Available at: https://taxguru.in/company-law/rotation-team-auditor-companies-act-2013.html [Accessed 24 Mar. 2025].

- taxguru_in and Khurana, C.A. (2014). Challenges for Auditor in Companies Act, 2013. [online] TaxGuru. Available at: https://taxguru.in/company-law/challenges-auditor-companies-act-2013.html [Accessed 24 Mar. 2025].

- https://www.taxmann.com. (2025). Available at: https://www.taxmann.com/research/company-and-sebi/top-story/105010000000013517/nuances-in-interpretation-of-provisions-of-rotation-of-auditors-under-the-companies-act-2013-experts-opinion [Accessed 24 Mar. 2025].