This article is written by Sanika Bhoite, PES Modern law college pune, during internship at LeDroit India.

Keywords –

Interim reliefs, civil suits, temporary injunctions, status quo

Abstract

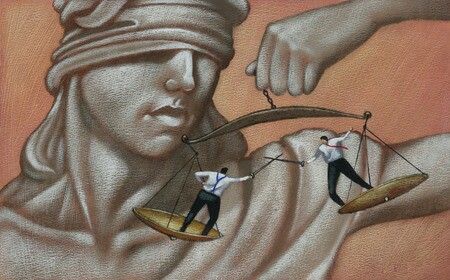

These mechanisms are pivotal in safeguarding rights during litigation in India. This article explores the scope and limitations of interim reliefs under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, and recent judicial trends as of 2025. Interim reliefs, such as temporary injunctions, stays, and receivership, aim to prevent irreparable harm and maintain the status quo until a final verdict. Recent rulings, like Bloomberg Television v. Zee Entertainment (2024), emphasize caution in defamation cases to protect free speech, while the Commercial Courts Act, 2015, prioritizes mediation in business disputes. Limitations include the temporary nature of reliefs, strict conditions, and risks of misuse in strategic lawsuits. Courts avoid orders resembling final judgments and face enforcement challenges. The Supreme Court’s 2025 clarifications, including rejecting automatic expiry of interim orders, highlight evolving judicial scrutiny.

1.

Interim Reliefs in Civil Suits: Scope and Limitations

India, civil suits over property, contracts, or defamation are everywhere—think neighbors fighting over land boundaries, businesses clashing over broken deals, or someone dragging another’s name through the mud. These disputes can drag on for years, and while the courts take their sweet time, people and companies face real damage: a builder might construct on disputed land, a rival could steal your brand’s customers, or false rumors could tank your reputation. Money can’t always fix these losses. That’s where interim reliefs step in—a quick court fix to pause the harm, protect your rights, or keep things as they are till the final verdict. But these reliefs aren’t easy to get, and they come with limits. In 2025, Indian courts are tightening the rules to ensure fairness, especially in defamation and business cases.

What is meant by Interim relief…?

Imagine Rajesh, a small shopkeeper in Delhi, who spent his life’s savings buying a plot of land for his family. But his neighbor, a powerful builder, claims the land is his and starts building a multi-story complex on it. Rajesh files a civil suit, but the court says it’ll take years to decide. Meanwhile, the builder keeps constructing, and Rajesh’s dream home slips away. If the court rules in his favor later, the building will already be up—money can’t undo that loss. This is the harsh reality of civil suits in India, where disputes over property, contracts, or defamation can ruin lives while cases drag on. “A party might eventually win the case but still suffer loss because the court did not protect the matter during litigation. This is why parties need interim relief. In simple terms, courts grant interim relief as a temporary remedy to safeguard either party’s interests before delivering the final judgment.” Whether it’s an order to restrain someone from selling a property or a direction to maintain the status quo, interim relief ensures that the eventual outcome of a case doesn’t become meaningless due to irreparable harm.

The primary goals of Interim relief are:

To preserve the status quo until a full trial is conducted.

To prevent irreparable injury to a party’s rights.

To ensure that the final decree is not rendered ineective.

To avoid misuse of process by parties with malafide intent.

These reliefs are governed primarily by the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (CPC) in India, under Order 39 (Temporary Injunctions) and Section 151 (Inherent Powers).

Historical Background of Interim Reliefs in India

“The common law tradition, inherited from the British legal system during colonial rule, firmly roots the concept of interim relief.” Before codification, Indian courts, particularly the Presidency Town civil courts and mofussil courts, relied on the principles of equity, justice, and good conscience when granting temporary protections. “English chancery courts influenced these principles and exercised the power to issue injunctions, appoint receivers, and grant temporary restraining orders.”

The need for interim remedies became more pronounced as civil disputes involving land, trade, and contractual obligations increased during the late 19th century. “Litigants often sought urgent judicial protection before courts could pass final judgments, especially in matters where delay could cause irreparable damage to their rights, property, or reputation.”

As India transitioned from colonial rule to independence, the use of interim reliefs expanded across civil domains, including family law, property, contract, consumer protection, and more recently, commercial disputes and intellectual property rights. Courts began using interim mechanisms not only to preserve rights but to also prevent misuse of judicial delay, especially in high-stakes litigation.

Notably, the Specific Relief Act, 1963 refined the statutory approach to injunctions—both temporary and permanent—complementing the CPC. It laid down the circumstances under which courts must refuse relief, such as when an equally effective remedy exists in the form of monetary compensation.

The evolution of Interim reliefs has thus been both statutory and judicial, shaped by colonial equity principles, refined by codified law, and continually adapted to the realities of Indian litigation. Today, interim orders remain a critical judicial tool, ensuring that the wheels of justice continue to turn even when the final verdict is far off

Interim Relief under Indian Law: A Snapshot

interim relief under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (CPC), and the Specific Relief Act, 1963, provides temporary remedies to preserve rights or prevent harm during litigation. Order 39, Rules 1-2 of the CPC empowers courts to issue temporary injunctions to halt actions like property sales or contract breaches, while Rule 6 permits interim sale of perishable goods. https://ledroitindia.in/

Order 25 mandates security deposits to cover potential losses, and Order 43, Rule 1® allows appeals against interim orders. Section 151 grants courts inherent powers for justice-driven orders. The Specific Relief Act, 1963 (Sections 36-42) governs temporary and permanent injunctions, with Section 38 preventing rights violations and Section 41 limiting relief when monetary compensation suffices.

Strategic Importance and Judicial Balance in Granting Interim Relief

Interim reliefs occupy a vital space in civil litigation as they offer immediate protection before a final verdict is delivered. These orders, though temporary in nature, can significantly impact the rights and liabilities of parties. The objective is not to grant a conclusive decision but to preserve the status quo, protect legal rights, and prevent any harm that could render the final decree meaningless.

A well-calibrated interim order can maintain judicial equilibrium and ensure that no party takes undue advantage of litigation delays. However, such powers must be exercised cautiously. Courts are required to balance competing interests — they must protect genuine grievances without encouraging frivolous or strategic litigation.

In practical terms, courts consider whether the party seeking relief has established a prima facie case, whether denial of relief will cause irreparable injury, and if the balance of convenience tilts in their favour. These three principles, rooted in equity, are not merely procedural checkboxes but foundational to ensuring fairness.

However, the grant of interim relief is not without criticism. In many instances, such orders are misused as stalling tactics. For example, a party may obtain an ex-parte injunction to block a project or freeze bank accounts and then prolong proceedings to harass the opposite party. Courts have become increasingly conscious of such abuse and have begun to penalize misuse through cost imposition and strict timelines for disposal.

Importantly, the Indian judiciary has evolved a body of precedent that guides lower courts in the careful application of interim relief principles. From contractual matters to property disputes and commercial arbitrations, courts have used interim reliefs to provide urgent remedies while ensuring that the final decision remains unaffected.

Courts apply a three-fold test (from Dalpat Kumar v. Prahlad Singh, 1992): a prima facie case, balance of convenience favoring the applicant, and irreparable injury without relief. This framework ensures equitable, temporary solutions pending final judgments

On What basis court Granting Interim Relief?

Courts typically assess the following to determine the scope and grant of interim relief :Prima Facie Case: The applicant must show a reasonable likelihood of success in the main case

.Balance of Convenience: The court weighs which party would suffer greater harm if relief is granted or denied.

Irreparable Injury: The applicant must demonstrate that without relief, they would suffer harm that cannot be remedied later

.Public Interest: In some cases, courts consider broader societal implications.

What is scope of interim relief?

Interim relief under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, and Specific Relief Act, 1963, includes various temporary remedies to protect rights during litigation. These encompass temporary injunctions (Order 39,

Rules 1-2) to halt actions like property sales or contract breaches, interim sale of perishable goods (Order 39, Rule 6), attachment before judgment to freeze assets (Order 38, Rule 5), appointment of receivers to manage disputed property (Order 40, Rule 1), security deposits to cover potential losses (Order 25), and stay orders to pause proceedings or actions. Courts may also use inherent powers (Section 151) for tailored relief and issue interim maintenance or custody orders in family disputes. These measures ensure the status quo or prevent irreparable harm until the case is resolved.

Limitations of Interim Reliefs

Despite their importance, interim reliefs have certain limitations:

a.

Not a Final Decision

They don’t determine rights conclusively – only preserve the matter till trial.

a.

Can Be Misused

Some litigants use interim reliefs to delay proceedings or harass the opposite party.

a.

Subject to Court’s Discretion

Even with strong claims, interim relief may be denied if the balance of convenience does not support the applicant.

a.

Duration and Enforcement

Many interim orders lapse or become ineffective due to non-compliance or delayed enforcement.

Section 151of cpc serves as a residual power. Even if no specific rule applies, courts can issue orders to: Stop abuse of process.

Grant urgent temporary protection.

Maintain court dignity.

However, Section 151 cannot override express provisions of the CPC or act in contradiction to statutory procedure.

Illustrations/Examples

1.Wander Ltd. V. Antox India Pvt. Ltd.

Citation: 1990 (Supp) SCC 727

In this case, Wander Ltd., a pharmaceutical company, sought an interim injunction against Antox India for using a deceptively similar trademark. “The trial court granted the injunction, and the opposing party challenged it on appeal. The Supreme Court held that judges exercise discretion when granting interim relief, and appellate courts should not interfere unless that discretion is arbitrary or perverse. This case firmly established that appellate courts must respect the trial court’s discretion in interim matters, thereby reinforcing judicial discipline.”

2.Dalpat Kumar v. Prahlad Singh

Citation: (1992) 1 SCC 719

The appellants in this case sought a temporary injunction to restrain interference with their possession of land. The trial court granted it, but the Supreme Court emphasized that interim injunctions should not be granted as a routine matter. Courts must first ensure that the applicant establishes a prima facie case, is likely to suffer irreparable injury, and that the balance of convenience lies in their favour. This case laid down the three essential tests for granting interim relief, which continue to guide Indian courts today.

Conclusion

In the high-stakes arena of Indian litigation, interim relief emerges as a powerful shield, safeguarding rights and halting chaos until the final gavel falls. Under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, and Specific Relief Act, 1963, courts deploy a dynamic arsenal—temporary injunctions to freeze property sales or contract breaches, asset attachment to thwart sly defendants, receivers to guard disputed estates, and interim sales to save perishable goods from rot. “The three-fold test—requiring a solid prima facie case, a tilt in the balance of convenience, and a risk of irreparable harm—ensures that courts do not grant relief lightly.” The Commercial Courts Act, 2015, adds a modern twist, pushing mediation but greenlighting urgent interim relief when time’s ticking. This isn’t just legal duct tape; it’s a masterstroke of justice, holding the line with precision. Interim relief, temporary injunctions, asset protection, status quo, and irreparable harm define this electrifying judicial dance, ensuring fairness doesn’t buckle under pressure.

References

Wander Ltd. & Anr. V. Antox India Pvt. Ltd., (1990) SuppSCC 727

https://indiankanoon.org/doc/330608

Dalpat Kumar & Anr. V. Prahlad Singh & Ors., (1992) 1SCC719