This article is written by Kimaya Anavkar, a T.Y.LL.B. student at Kishinchand chellaram Law College.

Abstract

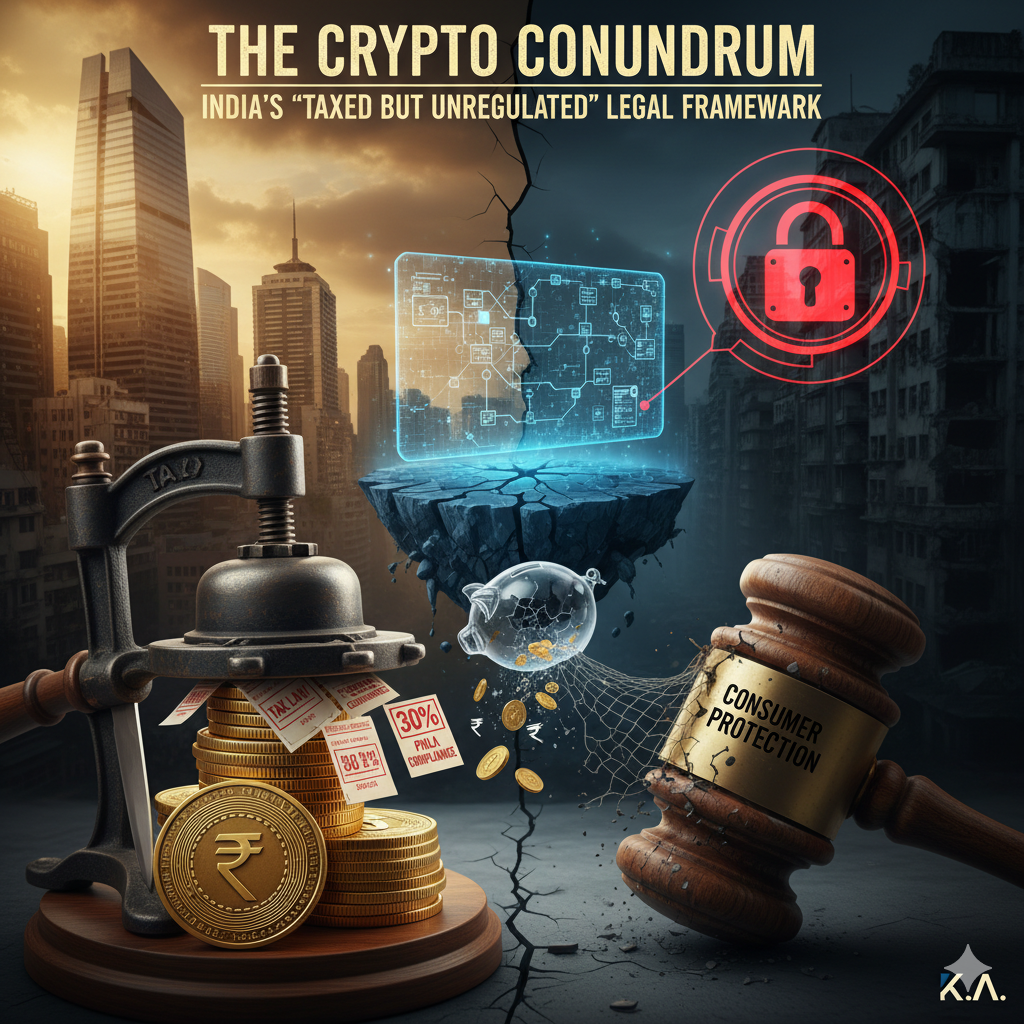

Cryptocurrency in India currently occupies a precarious legal space, characterized by a pragmatic, yet incomplete, regulatory approach. While the buying, selling, and holding of cryptocurrencies are deemed legal, they are not recognized as legal tender. This paper analyzes India’s dual control mechanism, which classifies crypto as a Virtual Digital Asset (VDA) under the Income Tax Act, 1961, subjecting it to stringent taxation, and simultaneously places it under the rigorous anti-money laundering (AML) compliance regime of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA).

It examines the landmark judicial interventions, particularly the Supreme Court’s corrective action in IAMAI vs. RBI and the recent recognition of crypto as ‘property’ by the Madras High Court. The article concludes that India operates in a regulatory paradox—effectively taxing and policing digital assets while lacking a comprehensive, dedicated consumer protection law, a lacuna that demands urgent legislative attention to balance innovation and financial stability.

1. Introduction: Cryptocurrency and the Sovereign Challenge

Cryptocurrency, a digital or virtual form of money secured by cryptographic techniques and operating on a decentralized ledger (blockchain), presents a fundamental challenge to the established monetary and regulatory authority of the State. The Indian government has chosen to classify these decentralized tokens as Virtual Digital Assets (VDAs). While the activity of trading and holding VDAs is legal, it is emphatically clear that they do not hold the status of legal tender. This nuanced position has necessitated the deployment of existing statutes to create a working, albeit piecemeal, regulatory structure.

2. The Legal Status and Judicial Intervention

India’s journey towards regulatory acceptance of crypto is primarily defined by a critical judicial review that overturned a complete ban.

2.1. The Landmark Judicial Foundation: IAMAI vs. RBI (2020)

In 2018, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) issued a circular that prohibited all entities regulated by it (i.e., banks and financial institutions) from providing any services to individuals or businesses dealing in cryptocurrencies. This was effectively a de facto ban, cutting off the crypto sector from the formal banking system.

The industry challenged this circular, which led to the landmark judgment of the Supreme Court in Internet and Mobile Association of India (IAMAI) vs. Reserve Bank of India (2020) 10 SCC 274. The apex court, in its historic ruling, set aside the RBI’s circular.

- The Principle of Proportionality: The Court held that while the RBI possessed the power to regulate, the complete prohibition failed the doctrine of proportionality. It noted that the RBI could not furnish a “modicum of evidence” demonstrating any actual or potential measurable systemic loss or harm to its regulated entities due to the operations of crypto exchanges.

- Constitutional Right: The judgment effectively restored the banking lifeline for the crypto ecosystem and implicitly protected the fundamental right of crypto-related businesses to carry on their trade, as guaranteed under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution of India. This decision is the cornerstone of the current legal landscape, making trading and holding cryptocurrencies permissible.

2.2. Judicial Recognition as ‘Property’: Rhutikumari v. Zanmai Labs (Madras HC, 2025)

In a major legal development, the Madras High Court, in the case of Rhutikumari v. Zanmai Labs (2025), recognized cryptocurrency as a form of “property” under Indian law.

- Legal Rationale: Justice N. Anand Venkatesh reasoned that property, as defined under the Constitution (e.g., in relation to Article 300A), extends to “every species of valuable right and interest.” By asserting that cryptocurrency has intrinsic value and is capable of being possessed and held, the Court concluded: “There can be no doubt that ‘cryptocurrency’ is a property.”

- Impact: This judicial clarity is vital for investor protection, allowing VDA owners to seek remedies, injunctions, and legal protection for their digital holdings in civil litigation, treating them as recoverable and seizable assets.

3. The Current Regulatory Framework: Tax and Anti-Money Laundering

The Indian government has chosen to regulate crypto not through a dedicated new law, but by amending two critical existing statutes.

3.1. Taxation under the Income Tax Act, 1961 (The Revenue Prism)

The Union Budget of 2022 introduced explicit provisions for the taxation of Virtual Digital Assets, making India’s tax regime one of the most stringent globally.

- Flat 30% Tax on Gain: Section 115BBH mandates a flat rate of 30% tax on any income arising from the transfer of a VDA. This rate is applicable irrespective of the taxpayer’s overall income slab or classification (e.g., as business income or capital gains).

- No Deductions/Loss Offset: This provision is particularly harsh as it explicitly disallows any deduction other than the cost of acquisition. Furthermore, losses from the transfer of a VDA cannot be set off against any other income (crypto or non-crypto) or carried forward.

- Transaction Tracking (TDS): Section 194S introduced a 1% Tax Deducted at Source (TDS) on payments made for the transfer of a VDA above a specified threshold. This mechanism serves as a comprehensive digital audit trail, ensuring that the government has a record of nearly all significant transactions within the crypto ecosystem.

3.2. AML Compliance under the PMLA, 2002 (The Surveillance Prism)

In March 2023, the Ministry of Finance issued a gazette notification bringing Virtual Digital Assets under the ambit of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002. This action dramatically elevated the compliance burden on the industry.

- Reporting Entities (REs): Entities providing services related to VDAs—including crypto exchanges, wallet providers, and custodians—are now officially designated as ‘Reporting Entities’ under the PMLA.

- FIU-IND Registration and Compliance: These REs are obligated to register with the Financial Intelligence Unit – India (FIU-IND). They must comply with rigorous Know Your Customer (KYC), Anti-Money Laundering (AML), and Combating Financing of Terrorism (CFT) standards, mirroring the requirements placed on banks and other traditional financial intermediaries.

- Reporting Obligations: The PMLA mandates REs to maintain detailed records of transactions and user identities, and, most importantly, file Suspicious Transaction Reports (STRs) with the FIU-IND for any potentially illicit activity. The Directorate of Enforcement (ED) has since actively utilized PMLA provisions to attach/freeze VDAs that are deemed to be ‘proceeds of crime,’ reinforcing the Act’s applicability.

4. Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the Digital Rupee

The RBI remains the most vocal critic of private cryptocurrencies, viewing them as a serious threat to financial and monetary sovereignty and stability. To mitigate this threat while embracing digital innovation, the RBI has developed its own digital currency.

- Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC): The RBI is actively piloting the Digital Rupee (e₹), which is the sovereign digital currency of India. Unlike private cryptocurrencies, the e₹ is a direct liability of the RBI, backed by the State, and is recognized as legal tender. It is intended to offer the technological efficiency of a digital currency without the volatility or regulatory risk associated with decentralized private tokens.

5. Conclusion: A Call for Legislative Clarity

India’s current legal framework is a study in ambivalence: it is heavily regulated in terms of taxation and AML/CFT compliance, yet entirely unregulated in terms of consumer protection, market supervision, and licensing requirements for exchanges. The proposed Cryptocurrency and Regulation of Official Digital Currency Bill, 2021 remains in legislative limbo.

The absence of a dedicated statute creates significant legal risks, particularly concerning market manipulation, investor fraud, and the jurisdiction of regulatory bodies like the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI). For the Indian crypto market to mature responsibly, legislative clarity is essential. The next step must be to move beyond indirect regulation to a comprehensive, dedicated legal framework that protects investors, provides a clear licensing pathway for legitimate businesses, and formalizes India’s position as a player in the global digital asset economy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Cryptocurrency Regulation in India

Q1. Is cryptocurrency legal in India? A. Yes. Buying, selling, and holding cryptocurrencies (Virtual Digital Assets or VDAs) is legal in India, though they are not recognized as legal tender.

Q2. Are cryptocurrencies legal tender? A. No. They cannot be used as official currency to pay for goods or services.

Q3. How is crypto income taxed? A. Profits from VDA transfers are taxed at a flat rate of 30% under Section 115BBH of the Income Tax Act, 1961.

Q4. Can I adjust crypto trading losses against other income? A. No. Losses from VDA trading cannot be set off against any other income.

Q5. What is the role of TDS in crypto transactions? A. A 1% Tax Deducted at Source (TDS) is mandated on VDA transactions above a specified limit, as per Section 194S, serving as a transaction tracking mechanism.

Q6. What is the significance of the PMLA, 2002? A. The Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) governs crypto exchanges, designating them as ‘Reporting Entities.’ This requires them to comply with strict AML/KYC norms and report suspicious transactions to the FIU-IND.

Q7. What was the IAMAI vs. RBI (2020) case about? A. The Supreme Court, in this landmark case, struck down the RBI’s 2018 circular that had banned banks from dealing with crypto entities, restoring banking services for the industry.

Q8. Is cryptocurrency considered ‘property’ in India? A. Judicially, yes. The Madras High Court recently recognized cryptocurrency as a form of ‘property’ capable of legal protection in the case of Rhutikumari v. Zanmai Labs.

Q9. What is the RBI’s alternative to private crypto? A. The RBI is piloting the Digital Rupee (e₹), which is the sovereign Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC), to provide a regulated digital alternative to private cryptocurrencies.