This article is written by Kimaya Anavkar, a T.Y.LL.B. student at Kishinchand chellaram Law College.

Keywords: CRISPR-Cas9, Gene Editing, Patent Law, Biotechnology, Broad Institute, UC Berkeley, Intellectual Property Rights.

Abstract

The revolutionary CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology has sparked one of the most significant patent disputes in modern science. This article delves into the core of the legal battle between the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and the University of California, Berkeley. It explores the central question: who truly invented the application of this groundbreaking tool for use in human and other eukaryotic cells? We will break down the complex legal distinction between a natural discovery and a patentable invention, reference key legal precedents that shape biotechnology patent law, and analyse the global implications for research, medicine, and commerce.

The conclusion reflects on how this monumental case will influence the future of innovation and patent strategies in the ever-evolving world of biotechnology.

Introduction: What is CRISPR-Cas9?

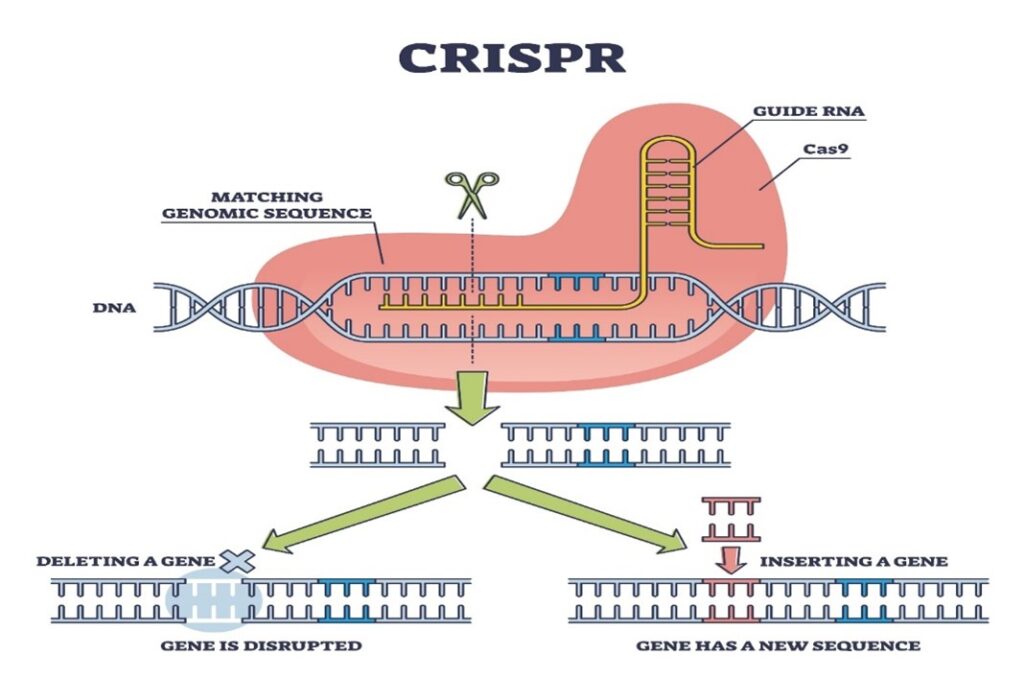

Imagine having a “find and replace” function for the very code of life, DNA. That is, in simple terms, the power of CRISPR-Cas9. This technology allows scientists to find a specific gene inside a cell and then edit, remove, or replace it with incredible precision. Its potential is revolutionary, offering the possibility of curing genetic diseases like cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anaemia, and even some forms of cancer.

This groundbreaking potential inevitably led to a high-stakes legal battle over who owns the rights to it. The central dispute involved two major academic powerhouses:

- The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley): Led by Jennifer Doudna and her collaborator Emmanuelle Charpentier.

- The Broad Institute: A joint venture of MIT and Harvard, with Feng Zhang leading their team.

Both groups filed patents related to CRISPR-Cas9, triggering a decade-long conflict to determine who had the right to claim ownership over this transformative technology.

The Core of the Dispute: Invention vs. Discovery

From a legal standpoint, the CRISPR patent war was not just about who discovered the technology first, but who invented its most valuable application.

The UC Berkeley team was the first to publish a paper in 2012 demonstrating how the CRISPR-Cas9 system could be used to cut DNA in a test tube. Their discovery was foundational. However, the Broad Institute team, a few months later, published research showing they had successfully adapted and used the CRISPR-Cas9 system to edit genes inside eukaryotic cells—the complex cell type found in plants, animals, and, most importantly, humans.

This distinction is crucial in patent law. The question became:

- Was UC Berkeley’s work a complete invention, with its application in human cells being an obvious next step?

- Or was the Broad Institute’s work of making it function in the much more complex environment of a eukaryotic cell a separate, inventive, and non-obvious step worthy of its own patent?

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) initially determined that the claims were distinct, allowing both parties to hold patents, but on different applications of the technology. This led to years of appeals and legal challenges over who had priority.

Patent Eligibility for Life Sciences: A Legal Tightrope

A central legal and ethical question in this field is whether one can patent life itself. The battle over CRISPR patents brings to mind landmark cases that have tried to draw this line. A key precedent is the U.S. Supreme Court case

Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc. (2013). In that case, the court ruled that simply isolating a naturally occurring human gene is not a patentable invention. However, it also ruled that creating a synthetic version of a gene (cDNA) could be patented because it was created by a scientist and not found in nature.

This “product of nature” doctrine was at the heart of the CRISPR dispute. UC Berkeley’s argument could be viewed as discovering a natural system. The Broad Institute countered that their adaptation of that system for a new, complex environment (eukaryotic cells) was an inventive act, creating something not found in nature—much like the distinction between a natural gene and a synthetic one in the Myriad case. This case highlights the fine line patent law must walk between rewarding groundbreaking research and preventing the monopolization of the fundamental building blocks of life.

Global Implications and Licensing

The CRISPR patent dispute was not confined to the United States. Patent offices around the world came to different conclusions, creating a complicated global landscape. For example, the European Patent Office (EPO) and courts in the United Kingdom often favoured the UC Berkeley/Charpentier claims, while the USPTO leaned towards the Broad Institute for the use of CRISPR in eukaryotes.

This fragmented ownership has significant consequences:

- For Researchers: Scientists often need to determine which patents apply to their specific work and which institution to approach for a license.

- For Companies: Biotech and pharmaceutical companies looking to develop CRISPR-based therapies have had to navigate this complex web, sometimes needing to license the technology from both parties to ensure they are not infringing on any patents. This can increase costs and slow down the commercialization of life-saving treatments.

Conclusion: The Future of Biotech Patents

After nearly a decade, the USPTO largely settled the main U.S. patent dispute in 2022 by upholding the Broad Institute’s key patents covering the use of CRISPR-Cas9 in eukaryotic cells. While the legal battles have subsided, their impact on biotech patent law remains. This case has underscored the critical importance of demonstrating a specific, practical application when you file for a patent, especially when the invention derives from a natural system. For law students and legal professionals, the CRISPR saga serves as a masterclass in the complexities of intellectual property in biotechnology.

It proves that in the race for innovation, the legal framework must constantly adapt to keep pace with science, ensuring that it continues to incentivize discovery without hindering progress. The future of gene editing is bright, but experts will continue to debate the legal questions it raises for years to come.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Can you legally patent a living thing?

Generally, no. You cannot patent something that constitutes a “product of nature,” like a newly discovered plant, a mineral, or a naturally occurring DNA sequence. However, you can often patent a life form after human intervention has significantly modified it, such as a genetically engineered microorganism that performs a new function. The key is the inventive step that creates something not found in nature.

2. Why does it matter who owns the CRISPR patent?

The owner of the patent has the legal right to control who can use the technology for commercial purposes, such as developing new medicines or agricultural products. They can charge licensing fees to companies, which generates revenue to fund more research. Ownership determines who profits from and controls this billion-dollar technology.

3. Is using CRISPR technology on humans legal?

It depends on the application. Using CRISPR for research in a lab (e.g., on human cells) is legal and common. Using it to develop therapies for diseases in a consenting adult patient (somatic cell editing) is also legal, and researchers are testing it in clinical trials. However, most countries ban or heavily restrict using it to edit human embryos or reproductive cells (germline editing), which passes changes to future generations, due to major ethical concerns.

4. From a legal standpoint, what happens if two people invent the same thing?

In the United States, the patent system operates on a “first-to-file” basis. This means that, in most cases, the law entitles the first person or entity to file a patent application for an invention to the patent, not necessarily the person who first invented it. This is why the filing dates of the UC Berkeley and Broad Institute patent applications were so critical in their dispute.