This article has been written by Manshi Raj, BBA – LL.B 3rd Year Student of Usha Martin University, Ranchi, Jharkhand during her internship at LeDroit India .

Keywords :

Adoption, Muslim Law, Guardianship, Islamic Jurisprudence, Shariat, Juvenile Justice Act.

Abstract :

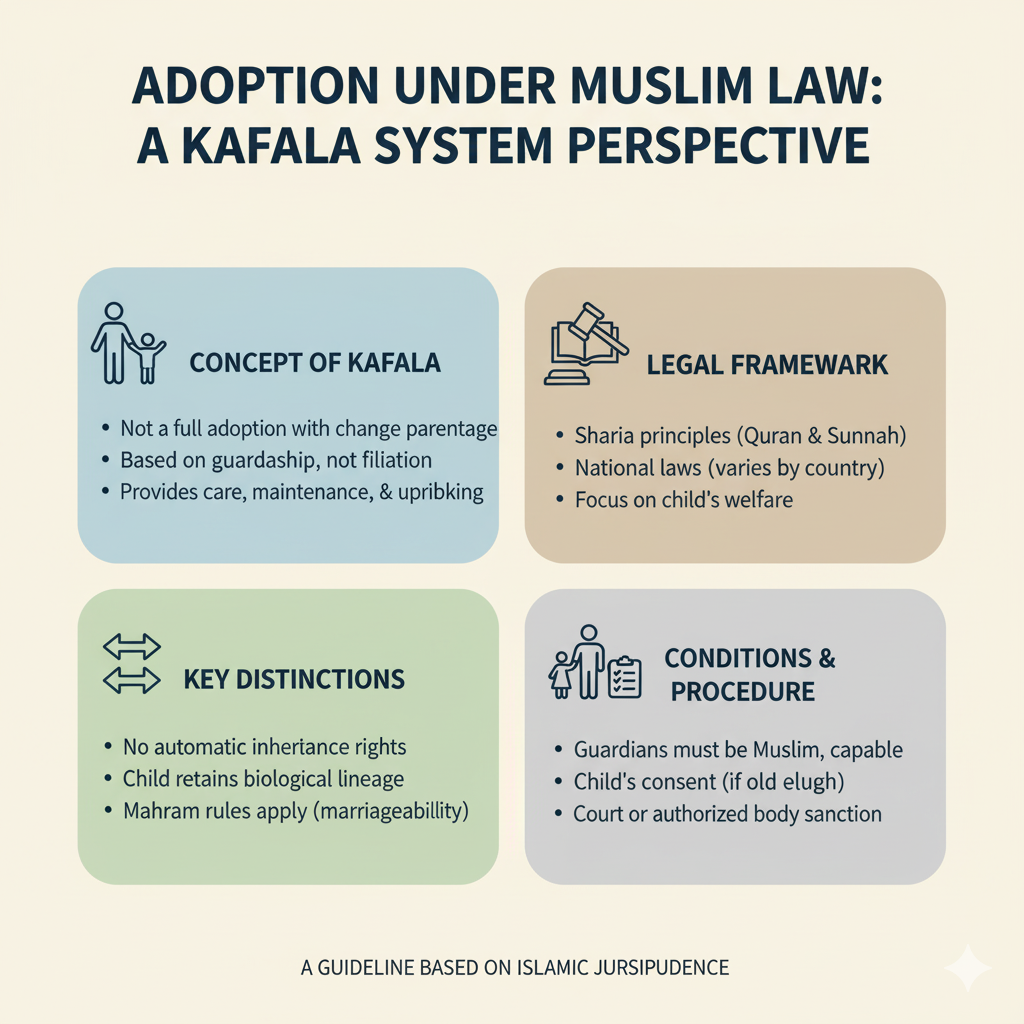

Muslim law on adoption is very different from other Indian personal laws. Islamic jurisprudence places more emphasis on guardianship (kafāla) than it does on adoption (tabannī), which is recognized in the same way as Hindu or secular laws. The Quran and Hadith uphold the distinction between biological and adoptive ancestry while emphasizing the value of providing for orphans. In Mohd. Allahabad Khan v. Mohammad Ismail (1929), the court upheld this principle by ruling that an adopted child does not inherit property from adoptive parents. There is a conflict between religious and legal provisions, though, because the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 permits Muslims to adopt under secular law. The legal framework, significant rulings, and ramifications of adoption under Muslim law in India are all examined in this essay.

Introduction ➖

The legal procedure through which a child acquires the same rights as a biological child and becomes the legal child of adoptive parents is known as adoption. Adoption is approached differently in different legal systems. For example, adoption is officially recognized by Hindu law, which gives the adopted child full inheritance rights. Adoption is permitted by both secular and Christian laws in India, guaranteeing the child’s legal equality. Adoption is not, however, recognized in the same manner under Muslim law. Rather, it encourages guardianship (kafāla), in which a child receives support and care but does not become a biological heir.

Due to the strict definitions of inheritance and lineage, adoption as it is known in other legal systems is prohibited under Islamic law. The Quran forbids altering a child’s biological identity. Rather than changing their legal parentage, guardianship enables a person or couple to raise and care for a child. For instance, under kafāla, a Muslim couple can care for an orphan and meet their needs without claiming the child as their legal heir. A case from real life is Shabnam Hashmi v. Union of India (2014), in which the Supreme Court decided that Muslims could adopt under the Juvenile Justice Act in spite of personal laws. This preserved the uniqueness of Islamic law while establishing a legal path for adoption.

Legal Provisions Governing Adoption under Muslim Law ➖

Islamic law does not recognize adoption in the same capacity as other legal systems. Guardianship is used instead to provide care for abandoned and orphan children. The Quran and the Hadith highlight the responsibilities of care of orphans and reason to retain a child’s identity if they are adopted or become a ward. For example, Surah Al-Ahzab (33:4-5) speaks to the need for orphans, or children who are adopted, should not be mistaken for an original born child; retain their original names. For example, the Prophet Muhammad designated Zayd ibn Harithah as his son, but Zayd retained his name. This is the Islamic example of guardianship, as opposed to eliminating the identification provided at birth.The Islamic replacement for adoption is Kafāla or guardianship. In this process, a guardian is responsible for a child’s care, education, and rearing a child, however, the child will remain limited in their ability to inherit. This maintains the principles of inheritance and lineage but will also provide the care of the child. In this way, a majority Muslim population who have followed the Islamic legal rules can take care of orphans through the Islamic rules set to guide taking care of orphans.

Under Muslim law, adoption and guardianship are clearly different. According to Hindu or secular laws, an adopted child has the same rights as a biological child, including the ability to inherit. However, guardianship (kafāla) does not confer inheritance rights under Islamic law; it merely offers care and protection. Given that Shariat law strictly governs inheritance in Islam, this distinction is noteworthy. An orphan raised by a Muslim couple under kafāla, for instance, will not automatically inherit their property unless they are given a specific gift or bequeathed a portion within the bounds permitted by Islamic law. This distinction allows for the welfare of orphaned children while maintaining the tenets of Islamic inheritance.

Judicial Precedents and Case Laws ➖

The case of Mohd. Allahabad Khan v. Mohammad Ismail (1929) AIR 1930 PC 209 has a landmark decision by that Court that under Muslim law an adopted child has no right to inherit from the adoptive parent. The Islamic court ruled that adoption, as understood in Hindu or civil law, is unacceptable in Islam. Instead, the child can be raised under guardianship, but his inheritance rights remain with the biological family. This case led to the theory that Islamic law maintains a sharp distinction between heirs and non-heirs.

In Shabnam Hashmi v. Union of India (2014) 4 SCC 1, The Supreme Court of India determined that under the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015, all citizens, including Muslims, could adopt. The petitioner, Shabnam Hashmi, wished to adopt, but was restricted by personal Muslim law. The Court held that the general secular law on adoption prevailed over personal law, and with this judgment, Muslims were allowed to legally adopt children. This was a landmark decision that allowed Muslims to adopt children while ensuring that the rights of the child were protected under secular law.

The Githa Hariharan v. Reserve Bank of India (1999) 2 SCC 228 case isrelated primarily to guardianship rights, but it had significant implications for child welfare legislation generally. The Supreme Court established as a precedent that a mother could be the natural guardian of a child. This was an important challenge to the idea that the natural guardian was always a father. Adopted by certain courts, the case did not address directly adoption of a child by a partner based on Muslim law, but was indicative of a call for more enlightened rules with respect to child custody and guardianship with the primacy of best interests of children.

Conflict Between Personal Law and Statutory Law ➖

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 recognizes adoption as a legal right for all Indian citizens, including Muslims. This poses a direct challenge to Muslim personal law, which does not recognize adoption in the same manner. Section 2(2) of the Act defines adoption as an irrevocable act of separation of a child from their biological parents and full rights granted to a child within their own family. This provision guarantees that the adopted child has the same legal and inheritance rights, whereas Islamic inheritance laws do not recognize adopted child status.

An important legal issue pertains to the relationship between secular law and personal law. The Supreme Court found in the Shabnam Hashmi v. Union of India case, that the Juvenile Justice Act applies to all citizens of India and grants Muslims an option to adopt through legal means. However, personal law is allowed by Article 25, which grants individuals freedom of religion. At the same time, this brings up the issue of whether applying secular and civil laws to personal matters infringes on one’s religious rights.

Muslim families encounter practical obstacles to adopting due to this legal conflict. If a family adopts under the Juvenile Justice Act, the adopted child will have full inheritance rights, which would not be congruous with Islamic law. However, should a family follow kafāla, then the child will not have legal status as an heir. This makes it more difficult to allow for guaranteed financial smoothness for the child. For instance, if a Muslim couple adopted and did so under secular law, there could be complications from religious authorities, whereas if a family adopted through kafāla, the family could struggle with obtaining legal documentation giving the child rights using kafāla. Additionally, this legal ambiguity would also jeopardize the welfare of orphaned children in Muslim families.

Illustrations and Examples ➖

Both Hindu law and Christian law recognize complete adoption under which the child will have the same status as a biological child. The Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956, provides for complete adoption with inheritance rights for the child. Christian couples may adopt under the secular Juvenile Justice Act. In Muslim law, the child does not have the same status as a biological heir, because the law is based on guardianship rather than adoption.

Take, for example, a Muslim couple who would like to adopt an orphan. If the couple acts according to Islamic law, they can take care of the child through guardianship, but the child cannot inherit from the couple. If the couple adopts under the Juvenile Justice Act, then the child is legally recognized as adopted but may face social and religious issues.

The Indian Penal Code (IPC) acknowledges the rights to guardianship as well. Section 361 of the IPC defines kidnapping as taking a minor out of lawful guardianship. This provision suggests the legal significance of guardianship in Indian law, which is consistent with the idea of kafāla in Islamic law.https://ledroitindia.in/changes-introduced-in-the-new-ipc/

Conclusion ➖

Though Islamic law does not allow for adoption in the literal sense, it does encourage guardianship as a suitable alternative to adoption. However, secular laws like the Juvenile Justice Act have come into existence allowing Muslims a different path to legal adoption. It has been consistently argued about the ongoing difficulty of weighing religious beliefs with the welfare of orphaned children. Court rulings, in cases such as Shabnam Hashmi, have been used to expand the scope of adoption rights, but continue to pioneer limitations on legal adoption under personal law. A reconsideration of the adoption laws in relation to Muslim families in India is urgently needed to protect children’s welfare under care and also respect individual religious autonomy.