This article is written by Neeraja Santhosh, 5th year, BBA-LLB(H), REVA University during her internship at LeDroit India.

Keywords: Creative Commons, copyright, licensing, attribution, non-commercial use, share-alike, no derivatives, open access, intellectual property.

Abstract

Creative Commons (CC) licenses have come to play a crucial role in managing copyright in the digital age, reconciling the historical rights of producers and authors with a need for wider dissemination and more liberal reuse of creative material. At its core, Creative Commons provides free, simple, and effective tools that let authors and artists license their creative work with a range of conditions for limited re-use Potential re-uses. This is in stark contrast to the all-rights reserved default of most copyright licenses, where only rights specifically granted elsewhere are retained by a reuser. CC licensing supports the idea of communing, or social practices that produce, use, and maintain public resources for collective good, most visibly in digital ecosystems around data, content, and IP. These licences are intended to be easy-to-use, and they allow creators to apply professionally drafted legal contracts to their works without possessing considerable legal knowledge.

Introduction

Creative Commons (CC) licenses have become increasingly important in the negotiation of rights in the age of digital reproduction and use, balancing between traditional producer and author rights and a desire for wider distribution and more flexible reuse of creative expression. Fundamentally, Creative Commons offers free, easy to use tools that let authors and artists set the specific terms on which they are willing to share their work, including the ability of others to copy, distribute and make use of it for non-commercial purposes. The organization was founded to address the gap between traditional copyright’s “all rights reserved” approach and the needs of the digital commons, where collaborative creation and knowledge sharing are paramount.

Historical Background of Creative Commons

Creative Commons was founded in 2001 by Lawrence Lessig, Hal Abelson, and Eric Eldred, with support from the Center for the Public Domain. The initiative emerged from growing concerns about the restrictiveness of traditional copyright law in the internet age. Lessig, a prominent legal scholar, had been involved in the Eldred v. Ashcroft case challenging the Copyright Term Extension Act.

The first set of Creative Commons licenses was released in December 2002, providing creators with a standardized way to grant permissions to their work while retaining certain rights. The project was inspired by the Free Software Foundation’s GNU General Public License and aimed to create a similar framework for creative and academic works. Over the years, Creative Commons has evolved from a U.S.-based project to a global movement, with licenses adapted to different legal jurisdictions through the Creative Commons International project. The current version, CC 4.0, released in 2013, represents the most internationally applicable and legally robust iteration of these licenses.

Types of Creative Commons Licenses

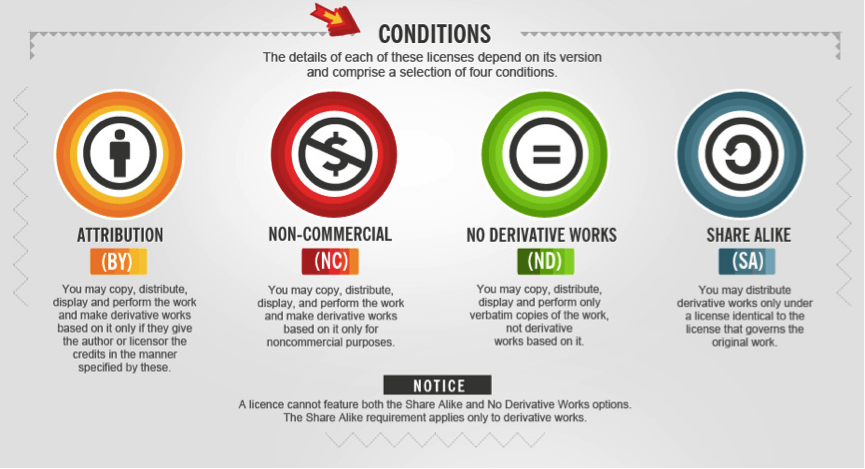

Four core elements of Creative Commons licenses are assembled from four basic conditions, which can be combined to create a number of licensing options:

- Attribution (BY): This is the least restrictive condition, requiring only acknowledgement of authorship.

- ShareAlike (SA): A work must be re-used under the same or a similar logo if it’s been modified, remixed, or adapted.

- Non-Commercial (NC): This restriction requires that the work must not be used for commercial purposes, this could include being used directly or indirectly to produce an income.

- No Derivatives (ND): The license prohibits the creation of derivatives, giving only exact reproductions to be distributed.

These four elements all come together under six main Creative Commons licences, each imposing a different level of restriction:

- CC BY (Attribution): The least restrictive of the six main licenses, allowing for reuse, remixing, adaptation and building upon your work even for commercial purposes as long as credit is given.

- CC BY-SA (Attribution-ShareAlike): Allows for remixing, adapting and creating on top of the material for any purpose, even commercially; provided that credit is given to the creator and any new works are licensed under similar terms.

- CC BY-ND (Attribution-No Derivatives): This allows redistribution of the work, both commercially and non-commercially, on the condition that the work is always fully attributed and not altered in any way.

- CC BY-NC (Attribution – Non-Commercial): This allows people to remix, adapt, and create new works based on original works for non-commercial purposes only. They must credit the author and keep the works non-commercial, but they do not have to use the exact same license.

- CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution-Non Commercial – ShareAlike): Under this license, others can remix, adapt, and build upon the work non-commercially, provided they credit the original author and license their new creations under identical terms.

- CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution-Non-Commercial – No Derivatives): The most restrictive CC license, permitting downloading and sharing of the work with attribution, but prohibiting any modifications or commercial use.

- CC0 Public Domain Dedication

In addition to these six, Creative Commons also provides CC0(CC Zero), a public domain dedication & waiver. That is, creators can waive their copyrights and related rights to the greatest extent possible worldwide, and anyone (not just the original creator) can use such a work for any purpose including commercially with no restriction of attribution or permission.

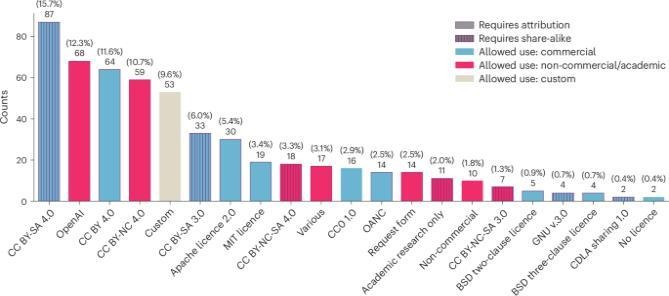

This chart shows the prevalence of different license types and their associated requirements, such as attribution, share-alike, commercial use, and non-commercial/academic use. For example, CC BY-SA 4.0 is a general license with a high number of attributions, share-alike, and diverse usage scenarios. CC BY-NC 4.0 focuses primarily on non-commercial and educational use. The presence of “custom” license types also suggests a significant number of unique, custom-defined terms in licensing practices. Furthermore, specific incompatibilities may arise between licenses, as evidenced by conflicts between proprietary and open-source licenses or even between different open-source licenses, often indicated by restrictions on distribution and modification.

CC Licenses and Copyright Law

Creative Commons licenses operate within the existing framework of copyright law rather than replacing it. They function as copyright licenses that grant permissions in advance, reducing transaction costs for both creators and users. The relationship between CC licenses and copyright law is founded on several key principles:

- Legal Foundation: CC licenses are built upon the copyright holder’s exclusive rights under Berne Convention principles and national copyright laws. A creator must own or control the copyright to a work before applying a CC license to it. The licenses do not diminish copyright; rather, they provide a standardized method for copyright holders to grant specific permissions while retaining other rights.

- Rights Granted vs. Rights Reserved: Traditional copyright operates on an “all rights reserved” basis, while CC licenses follow a “some rights reserved” approach. This means that instead of requiring users to seek permission for each use, CC licenses pre-authorize certain uses according to the license terms chosen by the creator. The copyright holder retains rights not explicitly granted under the license terms.

- International Applicability: The current 4.0 suite of licenses was designed to be internationally applicable, taking into account various copyright systems worldwide including both common law and civil law jurisdictions. The licenses account for related rights such as neighbouring rights and database rights, making them more comprehensive than earlier versions.

- Compatibility with Fair Use and Fair Dealing: CC licenses explicitly preserve users’ rights under fair use, fair dealing, and other copyright exceptions and limitations. Users may rely on these statutory rights regardless of the CC license applied to a work, and the license does not reduce or limit such rights.

Usage and Applications

Terms CC licenses are broadly used in a wide range of domains:

- Open Access Publishing (OA): They are the cornerstone of the open access movement, allowing access to research outputs for free. Major academic publishers and repositories like PLOS, arXiv, and institutional repositories worldwide use CC licenses to make scholarly work freely available while ensuring proper attribution.

- Open Educational Resources (OER):In education, they tackle copyright issues related to OER sharing and adaptation. Platforms like Khan Academy, MIT OpenCourseWare, and OER Commons utilize CC licenses to enable educators to freely use, adapt, and redistribute educational materials.

- Digital Humanities: For digital humanities, CC licenses handle intellectual property rights in a wide variety of creative works to foster collaboration among researchers, archivists, and cultural heritage institutions.

- Cultural Content Production and Distribution: They are employed by cultural institutions like Europeana, Smithsonian Institution, and various national libraries to digitize and distribute historical archives, making cultural heritage accessible to the public.

- Creative Industries: Musicians, photographers, filmmakers, and other artists use platforms like Flickr, SoundCloud, and Vimeo to share their work under CC licenses, building communities and enabling creative collaboration.

Creative Commons in India

The adoption of Creative Commons licenses in India has grown significantly over the past two decades, though it faces unique challenges within the Indian legal and cultural context.

- Legal Framework: India’s copyright law is governed by the Copyright Act, 1957 and subsequent amendments. CC licenses are legally valid in India as they operate within the existing copyright framework. However, there has been limited judicial interpretation of CC licenses in Indian courts, creating some uncertainty about enforcement.

- Adoption in Academia: Indian academic institutions have increasingly embraced open access publishing. The National Digital Library of India and various university repositories use CC licenses. The Indian Academy of Sciences publishes several journals under open access models using CC BY licenses.

- Government Initiatives: The Indian government has shown support for open access through initiatives like the National Knowledge Network and various e-learning platforms. However, the adoption of CC licenses in government-produced content remains inconsistent.

- Cultural Sector: Indian artists, musicians, and content creators have been slower to adopt CC licenses compared to Western counterparts, partly due to concerns about commercial exploitation and limited awareness of licensing options. Organizations like Access to Knowledge and Centre for Internet and Society have worked to promote understanding of CC licenses in India.

- Challenges Specific to India: These include limited copyright literacy, concerns about enforcement in a developing legal system, the tension between collective cultural traditions and individual authorship models, and inadequate infrastructure for digital rights management.

Creative Commons and Open Access Publishing

The relationship between Creative Commons licenses and open access publishing represents one of the most successful applications of the CC framework.

- The Open Access Movement: Open access aims to make scholarly research freely available online, removing price and permission barriers. CC licenses, particularly CC BY, have become the standard mechanism for implementing open access policies worldwide.

- Gold vs. Green Open Access: Gold open access refers to immediate free access through journals, typically using CC BY licenses. Major publishers like Springer Nature and PLOS use this model. Green open access involves self-archiving in repositories, where CC licenses help clarify reuse rights for archived versions.

- Funding Agency Requirements: Major research funders including the National Institutes of Health, European Commission, and Wellcome Trust now mandate open access publication with CC BY licenses for research they fund.

- Impact on Scholarly Communication: Studies have shown that open access articles receive more citations and broader readership. CC licenses enable text and data mining, accelerating research discovery and innovation.

- Challenges in Open Access: These include article processing charges creating new barriers, concerns about predatory publishers exploiting the open access model, and tensions between commercial publishers and the open access ethos.

- CC and Emerging Technologies (AI & Data)

- Creative Commons licenses face new questions and applications in the context of artificial intelligence and big data.

- Training Data for AI Models: A significant debate centers on whether using CC-licensed content to train AI models constitutes permitted use under the licenses. The CC BY license allows computational analysis, but questions arise about attribution when AI generates new content based on training data.

- AI-Generated Content: There’s ongoing discussion about whether AI-generated works can be licensed under CC, given questions about authorship and copyright ownership. Current copyright law in most jurisdictions requires human authorship for copyright protection.

- Data Sharing and Open Data: CC licenses, particularly CC0 and CC BY, are widely used for open data initiatives. Organizations like Open Data Commons and government open data portals use CC licenses to enable data reuse while ensuring attribution.

- Text and Data Mining: CC 4.0 licenses explicitly permit text and data mining, supporting computational research methods. This has proven crucial for fields like digital humanities, computational linguistics, and biomedical research.

- Machine Learning Ethics: The use of CC-licensed content in AI training raises ethical questions about whether such use aligns with creators’ original intentions, particularly for NC and ND licensed works. The AI community is grappling with developing ethical guidelines that respect CC license terms.

- Future Considerations: Creative Commons is actively working with the AI community to clarify how licenses apply to machine learning contexts. The CC community is discussing potential new licenses or clarifications specifically addressing AI applications.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite their benefits, CC licenses face challenges and limitations:

- Over-enthusiasm in licensing: Due to ease of use, this can lead to license selection misalignments where creators choose licenses without fully understanding the implications, potentially granting more rights than intended or imposing restrictions that limit beneficial uses.

- Copyright trolling: Attribution requirements can be exploited for financial gain, where individuals or entities acquire CC-licensed works and then aggressively pursue attribution violations for settlement payments, even for minor technical non-compliance.

- Ambiguity of the “Non-commercial” Condition: The definition of “non-commercial” can vary across jurisdictions and contexts, creating uncertainty. What constitutes commercial use in educational settings, government contexts, or advertising-supported platforms remains unclear and contested.

- Restrictions on Adaptability: The “No Derivatives” condition can stifle creative remixing and limit beneficial adaptations, particularly problematic for educational materials that may need modification for different contexts or accessibility requirements.

- Legal Nature and Jurisdictional Variations: Interpretation and enforcement can differ globally. While CC 4.0 licenses are designed for international applicability, differences in copyright systems, moral rights, and contract law across jurisdictions create challenges for consistent enforcement.

- Lack of Copyright Literacy: Among creators and users, limited understanding of copyright principles and CC license terms can lead to incorrect license selection, improper attribution, or inadvertent violations. Educational initiatives remain insufficient to address this knowledge gap.

- License Compatibility Issues: Different CC licenses may be incompatible with each other, particularly SA licenses with different versions or terms. This creates barriers to remixing and combining works, limiting collaborative potential.

- Revocability and Version Changes: While CC licenses are irrevocable for works already distributed, creators can change licenses for future distributions, creating confusion about which version applies to specific copies of a work.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Creative Commons licenses represent a crucial evolution in copyright law, offering a flexible and adaptable framework for managing intellectual property in the digital age. From their founding in 2001 to their current global adoption, CC licenses have fundamentally changed how creative and scholarly works are shared and reused. While their benefits in promoting open access and collaboration are undeniable, ongoing legal discourse and educational initiatives are essential to address their limitations and ensure their continued efficacy in balancing creator rights with the public interest.

The expansion of CC licenses into emerging technologies, particularly artificial intelligence and big data, presents both opportunities and challenges that will shape the future of digital commons. As adoption grows in diverse contexts from Indian academia to international research collaborations, the need for clear legal frameworks, improved copyright literacy, and thoughtful policy development becomes increasingly critical. Creative Commons licenses stand as a testament to the possibility of reimagining intellectual property for the digital age, enabling a more open, collaborative, and accessible knowledge ecosystem while respecting the rights and interests of creators.