This article is written by Anandi Chaturvedi of Chanakya Law College, Rudrapur,Uttrakhand [BA.LLB.-5th year] during her internship at LeDroit India

SCOPE OF ARTICLE

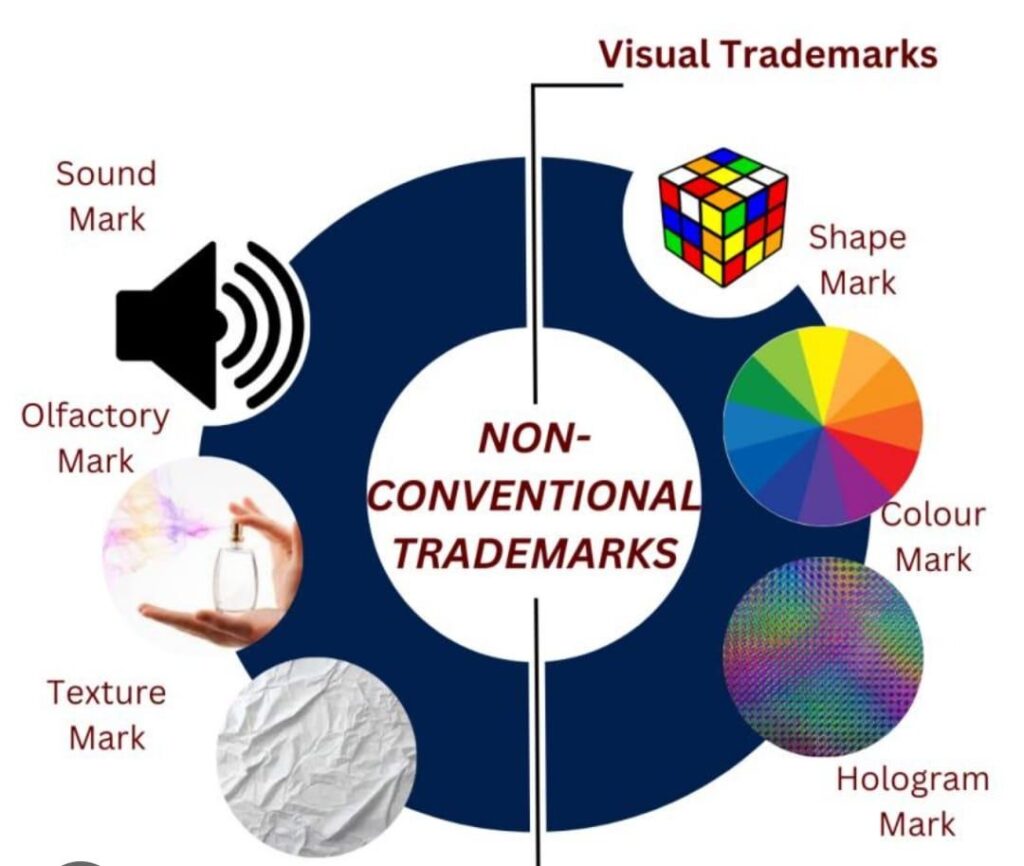

This article explores the evolving concept of non-conventional trademarks with particular emphasis on sound marks and smell marks. It analyses the shift in trademark law from traditional visual identifiers to sensory-based branding. The article examines the legal framework governing non-conventional trademarks in India under the Trade Marks Act, 1999 and the Trade Marks Rules, 2017, along with procedural requirements for registration.

It further discusses the challenges associated with the graphical representation of sound and smell marks, the application of the functionality doctrine, and relevant judicial interpretations. A comparative overview of international practices in the European Union and the United States is also undertaken to assess India’s position in the global trademark regime. The article concludes by highlighting emerging trends and the future prospects of sensory trademarks in India.

ABSTRACT

In the hyper-competitive global market, traditional trademarks consisting of words, logos, and symbols often struggle to capture the subconscious attention of consumers. This has paved the way for Non-Conventional Trademarks, specifically Sound Marks and Smell Marks, which leverage sensory branding to create instant brand recall. . This article delves into the burgeoning domain of sound and smell marks within India’s intellectual property framework. . It dissects the transition from the traditional “visual perception” requirement to the modern “graphical representation” standard.

It explores their definitions, the procedural intricacies of registration, and significant legal precedents. While sound marks have seen a clearer path to registration with the advent of the Trade Marks Rules, 2017, smell marks have historically faced challenges due to the stringent graphical representation requirement. However, recent developments, including the landmark acceptance of India’s first smell trademark for rose-scented tires, signal a progressive shift. The article also discusses that while sound marks have matured into a stable legal category, smell marks remain hampered by the lack of an objective, durable method of representation. The article concludes with recommendations for legal reform to accommodate the burgeoning “Sensory Economy.”

Keywords: Non-conventional Trademarks, Sound Marks, Smell Marks, Graphical Representation, Trademark registration India, Intellectual Property India, Trade Marks Act 1999

- The Genesis of Non-Conventional Trademarks

A trademark is essentially a badge of origin. Historically, under the TRIPS Agreement (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights), the definition of a trademark was centered on signs capable of distinguishing goods. However, Article 15 of TRIPS allowed member nations to require “visual perceptibility” as a condition for registration.

Traditionally, trademarks have been understood as visual symbols such as words, logos, or designs used to distinguish the goods or services of one enterprise from those of another. However, as markets become increasingly saturated and brands seek innovative ways to connect with consumers, the scope of what can be protected as a trademark has expanded significantly. This evolution has led to the recognition of “non-conventional” or “non-traditional” trademarks, which engage senses beyond sight.

- CONCEPT AND EVOLUTION OF SENSORY BRANDING

Sensory branding refers to branding strategies that engage one or more of the five human senses—sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. The objective is to create a strong emotional connection between the consumer and the brand.

Sound logos (such as jingles) and signature scents used in retail spaces are examples of sensory branding that have gained immense popularity. As a result, trademark law has gradually adapted to protect such identifiers, leading to the recognition of sound and smell as potential trademarks

As commerce evolved, the “visual” requirement became a bottleneck. Businesses realized that the human brain processes sound and smell faster than visual text. A Sound Mark (audio branding) or a Smell Mark (olfactory branding) can trigger an emotional response before a consumer even reads a label. Consequently, the legal definition of “mark” began to expand. In India, Section 2(1)(m) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999 includes “device, brand, heading, label, ticket, name, signature, word, letter, shape of goods, packaging or combination of colors.” While not explicitly mentioning sound or smell, the definition is inclusive rather than exhaustive.

- Sound Marks: Definition, Registration Process, & The Legalization of Jingles in India

A sound is a non-conventional trademark which is a unique sound or melody used by a business to identify the source of its products. Unlike a song protected by copyright, a sound mark must function as a “source identifier.”

While the Trade Marks Act, 1999, does not explicitly define sound marks, they are implicitly covered under the broader definition of a “mark” capable of being represented graphically and distinguishing goods or services. The Trade Marks Rules, 2017, significantly streamlined the registration process for sound marks by introducing a procedure that allows for the submission of sound recordings in MP3 format, along with a graphical representation, typically in the form of musical notation.

- Key aspects of sound mark registration in India:

- Application: An application for a sound mark must explicitly state that it is a sound mark.

- Graphical Representation: The primary challenge for sound marks was how to represent them on paper. In the case of Shield Mark BV v. Joost Kist, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled that describing a sound in words (e.g., “the crowing of a cock”) was insufficient. Instead, the sound must be represented by musical notations (staves, clefs, and notes)

- Audio Format: The sound must be submitted in an MP3 format, not exceeding 30 seconds in length.

- Distinctiveness: The sound must be distinctive and capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one entity from those of others. This often requires demonstrating “factual distinctiveness,” meaning the sound has immediate recall value associated with the product or service.

- Examples:

Yahoo’s Yodel: Yahoo was one of the first entities to obtain a sound mark registration in India in 2008 for its distinctive yodel.

ICICI Bank’s Jingle: ICICI Bank was the first Indian entity to register a sound mark for its corporate jingle.

Britannia Industries: The four-note bell sound associated with Britannia is another well-known registered sound mark.

Netflix ‘Ta-dum’ Sound: The iconic sound at the beginning of Netflix content has also been registered as a sound mark in India.

Nokia’s Tune: The distinctive Nokia tune has also been recognized as a sound mark.

The Trade Marks Rules, 2017, have made the registration of sound marks more accessible, leading to an increase in applications. However, the requirement of distinctiveness remains a crucial factor for registration.

- Smell Marks: The “Olfactory” Enigma

Smell marks, or olfactory marks, are trademarks where a specific scent is used to identify and distinguish the source of goods or services. A major legal hurdle for smell marks is the Doctrine of Functionality. A mark cannot be registered if the feature is essential to the use or purpose of the product.

- Example: A perfume manufacturer cannot trademark the scent of the perfume itself, as the scent is the product. However, a company selling “scented sewing thread” (where the scent is not necessary for the product’s function) may have a valid claim

- Hasbro’s Play-Doh: A registered scent mark covering Play-Doh’s distinctive fragrance, described in the registration record as a sweet, slightly musky vanilla-like aroma with additional notes that together create the familiar Play-Doh smell.

- Verizon Wireless Stores: A registered non-visual mark protecting a “flowery musk” fragrance used in Verizon Wireless retail outlets to create a consistent, recognisable in-store atmosphere.

- Bubble-Gum Scent for Footwear: A registered scent mark for “the scent of bubble gum” applied to certain footwear products, including shoes and sandals.

- Beer-Scented Darts: A historic UK trade mark registration for the “strong smell of bitter beer applied to flights for darts.”

- Key aspects of smell mark registration in India:

The Ralf Sieckmann v. Deutsches Patent- und Markenamt case established seven pillars for registration:

- Clear: The mark must be easily identifiable.

- Precise: No ambiguity in what the mark represents.

- Self-contained: The representation must stand on its own.

- Easily Accessible: Understandable by the public and authorities.

- Intelligible: Must make sense to a person.

- Durable: Must not fade or change over time.

- Objective: Not based on subjective human perception.

Most smell marks fail the “durable” and “objective” tests. Chemical formulas represent the substance, not the smell; odor samples decay over time; and written descriptions (e.g., “the smell of a rose”) are too subjective.

- Landmark and Recent Cases:

Sumitomo Rubber Industries Ltd. (Rose-Scented Tyres: In a pioneering decision in November 2025, the Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks accepted India’s first smell trademark application for a “floral fragrance/smell reminiscent of roses applied to tyres”. This application, filed in March 2023, was accepted after extensive scientific evidence and technical graphical representation were provided. The Registry concluded that the scent was clearly, precisely, intelligibly, and objectively represented, functioning as a unique identifier for the brand. This case sets a significant precedent for olfactory marks in India.

While previously smell marks were largely unexplored and considered practically impossible to register due to representation challenges, the Sumitomo case signifies a major shift, indicating India’s evolving approach to non-conventional trademarks.

The “Freshly Cut Grass” Case (Venootschap onder Firma Senta v. G.H.B. Ltd)

The first smell mark in the EU was for “the smell of freshly cut grass” applied to tennis balls. The Office for Harmonization in the Internal Market (OHIM) initially accepted it, arguing that everyone knows what freshly cut grass smells like. However, this was prior to the stricter Sieckmann ruling. Since Sieckmann, such registrations have become nearly impossible

- Technical Challenges in Registration

- The Problem of Subjectivity

In the Indian Kanoon – Trademark Disputes, many disputes arise because sensory perception is subjective. What sounds like a “pleasant jingle” to one might be “noise” to another. For smells, the human nose suffers from “olfactory fatigue,” making it difficult for trademark examiners to consistently verify a mark.

- The Difficulty of Search

Traditional trademarks are searched via text databases. How does a new business search for existing sound or smell marks to avoid infringement? Currently, there is no effective “Search by Scent” or “Search by Sound” algorithm in the Indian Trademark Registry, leading to potential “IP thickets.”

- Expanding the Scope: Moving Towards a “Scent-less” Registry?

In 2017, the EU removed the requirement for “graphical representation,” allowing applicants to submit digital files (MP3 or MP4). India has partially adopted this by requiring MP3s. However, the Indian Registry still insists on a graphical notation. This creates a “double burden” for non-musicians who wish to register sounds that are not musical (e.g., the sound of a closing car door).

- The Future of Sensory Marks

With the rise of the Metaverse and Web 3.0, non-conventional marks will become the primary way brands interact with users. We are likely to see:

• Motion Marks: Moving logos.

• Tactile Marks: The specific “feel” of a product’s texture.

• Haptic Trademarks: Patterns of vibration in smartphones.

As AI improves, we may see the development of “digital scent signatures”—a way to represent smells through precise data points that satisfy the Sieckmann requirement for being “objective” and “durable.”

- Comparative Jurisprudence: Global Approaches to Non-Conventional Trademarks

The treatment of non-conventional trademarks varies significantly across jurisdictions, reflecting differing levels of technological preparedness and legal flexibility. A comparative analysis of global approaches provides valuable insight into how India may further refine its legal framework.

In the European Union, the removal of the graphical representation requirement under the EU Trade Mark Regulation marked a significant shift in trademark jurisprudence. The EU Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) now allows trademarks to be represented in any form that enables authorities and the public to determine the subject matter of protection clearly and precisely. This reform has facilitated the registration of sound marks through audio files and has opened the door for other non-traditional marks, provided they meet the criteria of clarity, precision, durability, and objectivity. However, despite this progressive approach, smell marks remain practically unattainable due to the lack of reliable sensory recording mechanisms.

In the United States, trademark protection is governed by the Lanham Act, which does not explicitly exclude non-visual marks. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has recognized sound marks and, in rare cases, scent marks, provided they serve no functional purpose and have acquired distinctiveness. The registration of scent marks such as the plumeria-scented yarn demonstrates a comparatively flexible approach. However, similar to India and the EU, functionality and evidentiary challenges significantly restrict widespread recognition.

In contrast, India occupies a transitional position. While the Trade Marks Rules, 2017 have modernized procedural aspects—particularly concerning sound marks—the absence of statutory clarity on smell marks continues to hinder their recognition. Unlike the EU, India still mandates graphical representation, thereby limiting technological flexibility. Nevertheless, recent administrative openness, as reflected in the acceptance of the rose-scented tyre mark, signals a willingness to evolve.

This comparative perspective highlights that while India may not yet be at the forefront of non-conventional trademark protection, it is gradually aligning with international developments. With strategic regulatory amendments and technological integration, India has the potential to emerge as a progressive jurisdiction in sensory trademark recognition.

- Strengthening the Legal Framework: Policy Considerations

For India to fully harness the commercial and legal potential of non-conventional trademarks, certain policy reforms merit consideration. First, the removal or relaxation of the graphical representation requirement would significantly enhance accessibility for applicants, particularly for non-musical sounds and olfactory marks. Second, the introduction of standardized digital repositories for sound and scent files would promote transparency and improve trademark search mechanisms. Third, examiner training in sensory trademark assessment would ensure consistent and informed decision-making.

Furthermore, the integration of scientific expertise—such as chemical profiling for scents or waveform analysis for sounds—could bridge the gap between subjective perception and objective evaluation. These reforms would not only streamline the registration process but also reduce uncertainty for brand owners seeking to protect innovative identifiers.

Ultimately, embracing technological advancements while maintaining legal certainty will be crucial in shaping a future-ready trademark regime.

- Future Prospects:

Evolving Legal Framework: The acceptance of India’s first smell trademark demonstrates the adaptability of the Indian trademark law framework to embrace new forms of branding.

Technological Advancements: The use of scientific and technical methods for representation, as seen in the Sumitomo case, will likely pave the way for the registration of more complex non-conventional marks.

Increased Innovation in Branding: As businesses increasingly rely on sensory experiences for brand differentiation, the recognition of non-conventional trademarks will encourage more innovative branding strategies.

Global Harmonization: India’s progressive stance aligns it with international trends, ensuring Indian businesses are competitive in the global marketplace

- CONCLUSION

Non-conventional trademarks represent the frontier of Intellectual Property law. While the Trade Marks Act, 1999 was originally drafted with visual marks in mind, the Trade Marks Rules, 2017 have shown a commendable ability to adapt to the digital age, particularly regarding Sound Marks. However, the legal regime for Smell Marks remains in its infancy, trapped by the limitations of graphical representation. For India to become a global IP hub, the Registry must consider moving away from the rigid “graphical” requirement for all sensory marks and embrace purely digital filing. Until then, businesses should focus on “acquired distinctiveness”—ensuring that their sounds and scents are so famous that the public instantly connects them to the brand, thereby overcoming technical registration hurdles.