This article is written by Soumyadeep Biswas, studying at University of Calcutta, B.A. L.L.B. 3RD Year during his internship at LeDroit India.

Keywords

Arbitral Award, Section 34, Arbitration Act 1996, Public Policy, Patent Illegality, Judicial Review

Abstract

Section 34 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, provides the mechanism for challenging arbitral awards, which essentially balances principles of fairness, party autonomy, and procedural integrity in the arbitral process. The scheme under Section 34 provides for recourse to courts invoking limited and specific grounds such as public policy, patent illegality, fraud, corruption, incapacity, and failure of natural justice. These enumerated grounds reflect essential arbitration keywords such as arbitral award, public policy, and judicial review. The Indian judiciary has laid emphasis on minimum interference, which has been further strengthened by the amendments in 2015 and 2019 as part of the policy of pro-arbitration.

The present article undertakes a detailed analysis of each ground under Section 34 with the aid of landmark cases such as ONGC v. Saw Pipes, Associate Builders v. DDA, and SSangyong Engineering v. NHAI, together with recent developments. Key illustrations, practical challenges, and emerging jurisprudence will also be brought to light in this discussion, shaping India’s arbitral contours.

Introduction

From being the preferred mechanism of dispute resolution in commercial matters throughout India, arbitration has gained this preference principally for its inherent advantages of speed, procedural flexibility, confidentiality, and cost-effectiveness as compared to traditional litigation. The pro-arbitration policy reflected in the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, coupled with judicial inclination toward minimal interference, has further strengthened India’s position as a growing arbitration-friendly jurisdiction. Despite this autonomy granted to parties and arbitrators, the enforceability and finality of an arbitral award are not absolute. The legal system provides checks and balances to ensure that the arbitral process is conducted with fairness, legality, and the public interest.

Section 34 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 provides the only statutory remedy available for challenging an arbitral award in India. It enumerates specific, narrow, and well-defined grounds on which alone an award may be set aside, including lack of due process, invalidity of the arbitration agreement, excess of jurisdiction, fraud, corruption, contravention of public policy, and patent illegality. These grounds operate as necessary checks against arbitral misconduct while simultaneously ensuring that courts do not reappreciate evidence or assume appellate jurisdiction over awards. This article examines the scope, philosophy, and judicial understanding of Section 34, demonstrating how Indian courts balance party autonomy with limited judicial review as a means to ensure the integrity of the arbitral system is upheld.

Legislative Framework of Section 34

Section 34 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 draws its foundation from the UNCITRAL Model Law, which emphasizes minimal judicial intervention and maximum party autonomy. It introduces narrow, exhaustive, and clearly enumerated grounds on which an arbitral award may be set aside, ensuring that the courts do not function as appellate authorities over arbitral decisions. While an appeal is a comprehensive review by a higher court of facts, evidence, and legal reasoning, a petition under Section 34 is a summary proceeding. Courts are restricted to examining only whether the award violates statutory safeguards such as jurisdictional limits, procedural fairness, or fundamental legal principles. They are expressly prohibited from reassessing evidence, reinterpreting contractual terms, or substituting their own view for that of the arbitral tribunal.

Such a narrow framework of judicial review is essential to maintaining the sanctity, finality, and efficaciousness of arbitration. Excessive intervention defeats the very object of engaging in arbitration as a means of dispute resolution and depreciates confidence in the process. By limiting intervention only to cases that reach the threshold of fraud, corruption, violation of natural justice, patent illegality, or case conflict with public policy, Section 34 achieves a considered balance between the correction of injustice and upholding arbitral autonomy, thus facilitating stability and certainty in commercial dispute resolution.

Objectives of Section 34

Section 34 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 is an important check in India’s arbitral system, protecting both the validity of arbitral awards and efficiency in alternative dispute settlement. Its primary function is to ensure the validity of an arbitral award, whereby the courts can set aside, on certain grounds, an award tainted with fundamental defects, bias, due process, excess of jurisdiction, or even against Indian public policy. This limited judicial review ensures that parties are not compelled by a binding award, which is either tenuous on legal grounds or just not fair.

Another important purpose is the prevention of miscarriage of justice. While arbitration favors speed and flexibility, Section 34 ensures that procedural irregularities or substantive injustices do not go unchecked. This is a corrective mechanism against awards obtained through fraud, corruption, or breaches of natural justice.

In tandem, the provision is framed so as to limit judicial intervention. The courts are expressively precluded from reviewing the merits of the dispute with a view to preserving the autonomy and finality of arbitration. This creates the necessary balance between party autonomy and public interest that must exist for arbitration to remain effective, while also remaining consonant with wider constitutional and legal provisions.

Nature of Judicial Intervention

The Courts have emphasized through a number of decisions over the years that Section 34 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act of 1996 does not permit the re-examination by Courts of the evidence or merits of an Arbitral Award (as an appellate Court would). Rather, Section 34 should be narrowly construed by Courts to restrict their review of Arbitral Awards to only the types of error expressly stated in Section 34(2), including violations of natural justice, institutional errors of jurisdiction, and violations of public policy, in order to uphold the finality and autonomy of the arbitration process and to prevent a Court from interfering in relation to the award because it has reached a different conclusion from that of the Arbitrator.

A recent illustration of the Supreme Court’s position on this matter is found in the Associate Builders v. DDA case, where the Supreme Court on the facts of that case rejected the proposition that the judiciary could reassess the facts or re-interpret the terms of a contract or substitute its own assessment for that of the Arbitrator. The Supreme Court reinforced the importance of arbitration as an expedient alternative to the protracted proceedings of the Courts; thus, the purpose of court review of an arbitration award is limited to a supervisory function rather than being on an appellate level. Courts should only interfere with an award where the award is so irrational or perverse that it shocks the conscience of the Court.

As a result, Section 34 sets out parameters to ensure that the arbitration process operates effectively, efficiently, and independently and that the Courts do not intervene unnecessarily in maintaining the integrity of the arbitral tribunal.

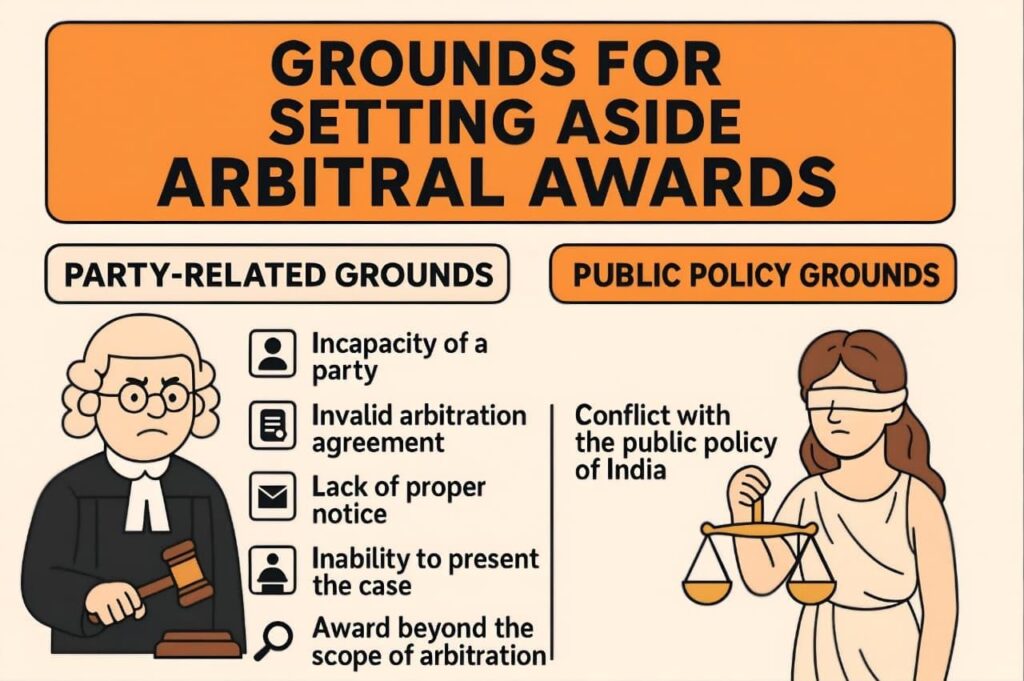

Grounds for Setting Aside an Arbitral Award

Incapacity of the Parties

The capacity of the parties is a critical component to the establishment of a valid arbitration. If a party does not have the capacity to enter into an arbitration agreement; for example, if that party is a minor, found to be mentally ill or otherwise disqualified under the law of contracts, then that arbitration agreement is rendered defective. Section 34(2)(a)(i) is concerned with the fact that the essential element of consent must be present when the parties agree to arbitration, and that consent must be genuine and legally valid. Consequently, the courts regard incapacity very strictly because it undermines the ability to provide for incorporeal equity and the autonomy of the arbitration process from the very beginning of the process.

Example: In the case where a minor participates in arbitration and signs an arbitration agreement and the minor has no legally appointed guardian, any award resulting from such participation will be voided because the minor had no legal capacity. Even if the hearings were otherwise held properly, the incapacity of the party would void any award given.

Invalid Arbitration Agreement

Each arbitration agreement creates the jurisdiction upon which a tribunal must base its authority. If the arbitration agreement is found to be invalid due to missing documents (i.e., stamping), deceit/duress, ambiguity, violation of statutory requirements and so forth, the resulting award cannot be enforced. The court in the case of N.N. Global Mercantile vs. Indo Unique Flame, ruled that the absence of a stamped document limits available enforceability for any arbitration award, as well as impacting the powers of the tribunal and the validity of any resulting award. The principle of establishing jurisdiction, which comes from the contract nature of the agreement, will restrain the enforcement of any agreement that is invalid.

Example: where an arbitration clause is contained in a poorly stamped contract results in the arbitrator having no jurisdiction from the very beginning which in turn causes the award to be annulled.

Lack of Proper Notice or Inability to Present Case

If an arbitration is to be fair, it should follow the rules of natural justice, which include the right to fair hearing. Section 34(2)(a)(iii) mentions situations where a party:

did not get proper notice about the appointment of the arbitrator,

did not get notice about hearings or

was not allowed to present evidence or arguments.

Judicial decisions regard natural justice violations as major concerns because they destroy the procedural integrity of the arbitration.

Illustration: The award is very likely to be challenged if the arbitrator prohibits cross-examination of a central witness or denies submission of crucial evidence by that party.

Award Deals with Matters Beyond the Scope of Submission

Arbitrators get their authority only from the matters referred to them. If an arbitrator takes a decision on matters outside the reference, for instance, by granting unclaimed relief or interpreting outside the contract, he/she has gone beyond the jurisdiction. The Supreme Court, in MSK Projects v. State of Rajasthan, ruled that such a power quirk renders the award in part or fully invalid.

This reason still supports the concept that arbitration is a voluntary process and its domain is purely defined by the parties’ agreement.

Unjust Establishment of the Arbitration Tribunal

The arbitral agreement typically stipulates the methods through which an arbitral tribunal can be created. Any materials used in this process that do not comply with the stipulations of the institutional rules or that have been appointed in an invalid manner will result in an arbitrarily established tribunal that can be requested for cancellation under 34(2) a v through a court of law.

This establishes objectivity and equality for the parties to the arbitration as well as compliance with the statutes in existence for the establishment of a tribunal.

Award Created by Fraud or Bribery

Fraud and bribery are at the heart of the denial of justice. If any award or decision has been obtained through fraud, bribery, omission of material facts or fraudulent manipulation of evidence, the court will consider the award to be void. The courts have made significant changes to ensure that the courts do not condone or promote any activity associated with fraud, corruption or bribery.

Legal Violation of Indian Public Policy

The scope of the term public policy is limited but, it is still a very important basis for a request for an annulment of an award. The Supreme Court in the case of ONGC v. Saw Pipes has expanded the definition of public policy to encompass:

The basic tenets of Indian law

Justice or morality

An award created through fraud or corruption

Awards that breach any of the statutory law, promote or endorse illicit acts or unethical conduct may be rejected by a court as violating public policy. However, the courts will give priority to protecting the integrity of public policy.

Patent Illegality (Domestic Arbitration Awards Only)

A definition of patent illegality was set out by the court in Ssangyong Engineering v. NHAI. Patent illegality refers to errors that are so obvious that they can be seen directly on the face of the award, including:

1. Contradiction of mandatory law;

2. Total disregard of significant evidence; and

3. A decision which no reasonable person could have arrived at.

Courts have no authority to review or amend evidence to rectify minor legal errors, but the prohibition on awards based on patent illegality serves to prohibit a type of award that results from an irrational process, while limiting court involvement to the minimum.

Recent Judicial Trends (Post-2015 & 2019 Amendments)

A major shift in the judicial scenario regarding Section 34 has occurred due to the 2015 and 2019 amendments, which have routed Indian arbitration firmly to a pro-arbitration framework. The one such shift is the reduction of the “public policy” ground, which was, in fact, a broad gateway for challenges previously. The courts interpret public policy in a very limitative manner and do interventions only in cases of fraud, bribery, revocation of fundamental legal rights, or shocks to justice. Thus, it is ensured that the parties cannot take advantage of the provision to bring back the factual disputes.

In addition, a major trend is the judiciary’s promptness in dealing with Section 34 petitions, which was accentuated by the installation of Section 34(5) that requires quick hearings after notice is given. The High Courts of the entire country have habitually pointed out the importance of complying with the legal time limits, thus cutting down the time taken by the prolonged challenges that hitherto presented difficulties in enforcement.

Most importantly, the courts always affirm that Section 34 does not mean an appeal concerning its merits. The courts do not go through the process of giving a new value to the evidence, changing the interpretation, or guessing what the arbitrator has come to because of the reasoning he or she used. This is in line with the arbitration standards prevailing globally, and it thus strengthens India’s position as an arbitration hub.

Practical Challenges in Section 34 Petitions

The Section 34 petitions proceedings still face a number of hurdles after the introduction of major reforms that undermine the very essence of arbitration as a fast dispute-resolution mechanism. One of the main factors is the delay due to insufficient judicial infrastructure. The absence of proper arbitration benches in most of the courts leads to the buildup of cases and the assignment of slow schedules for hearings. The delay often negates the purpose of the provision meant for expeditious review as per Section 34(5).

Another difficulty is the obstruction of Section 34 for the purpose of a hidden appeal. The courts have been burdened with the redoing of the testimony, and the reexamination of the evidence by the parties despite the fact they have been told that Section 34 is a very limited supervisory remedy. This practice increases the load on the courts and at the same time undermines the independence of arbitration.

The situation is made worse by the lack of judges who are experts in arbitration law. The technicalities involved in complex commercial disputes often require a very deep understanding of the matter, but that might not always be the case with general civil courts, who do not always convey the arbitration issues with the needed precision, thus resulting in inconsistent jurisprudence and long litigations.

Finally, the courts are more than ever before hounded by the issues of documentation and procedural requirements. The adjudication process is severely delayed by the large petitions, many annexures, and extensive records. All these challenges together limit the efficiency of Section 34 and provide a strong case for the need of simplified procedures, establishment of arbitration courts, and more stringent judicial control to maintain the speed and reputation of arbitration in India.

Conclusion

The cornerstone of judicial oversight in India’s arbitration framework is provided by Section 34, the arbitral awards are ensured to be in accordance with the essential standards of fairness, legality, and procedural integrity. It is a provision that maintains a delicate balance between correcting injustice and preserving the finality of awards by limiting the grounds of challenge to such clearly defined categories as public policy, fraud, jurisdictional defects, and patent illegality. The post-amendment judicial approach characterized by minimal interference and strict adherence to statutory limits has been a great contributor to the building of trust in arbitration as a reliable dispute-resolution mechanism. Courts now affirm with regularity that Section 34 is not an appellate remedy which in turn strengthens party autonomy and reduces the number of frivolous challenges. A greater synchronization in the interpretation of High Court decisions is however still very much required. The successful and uniform application of Section 34 in India’s role as a global arbitration hub would be the main contributor to the commercial certainty, efficiency, and trust in the arbitral process.